Presentation by NORRAG at UKFIET 2017 on the Contribution of Large Scale Assessments to the Monitoring of SDGs by Patrick Montjouridès

The Contribution of Large Scale Assessments to the Monitoring of Sustainable Development Goals by Patrick Montjouridès, NORRAG

International Large Scale Assessments in the global development agenda

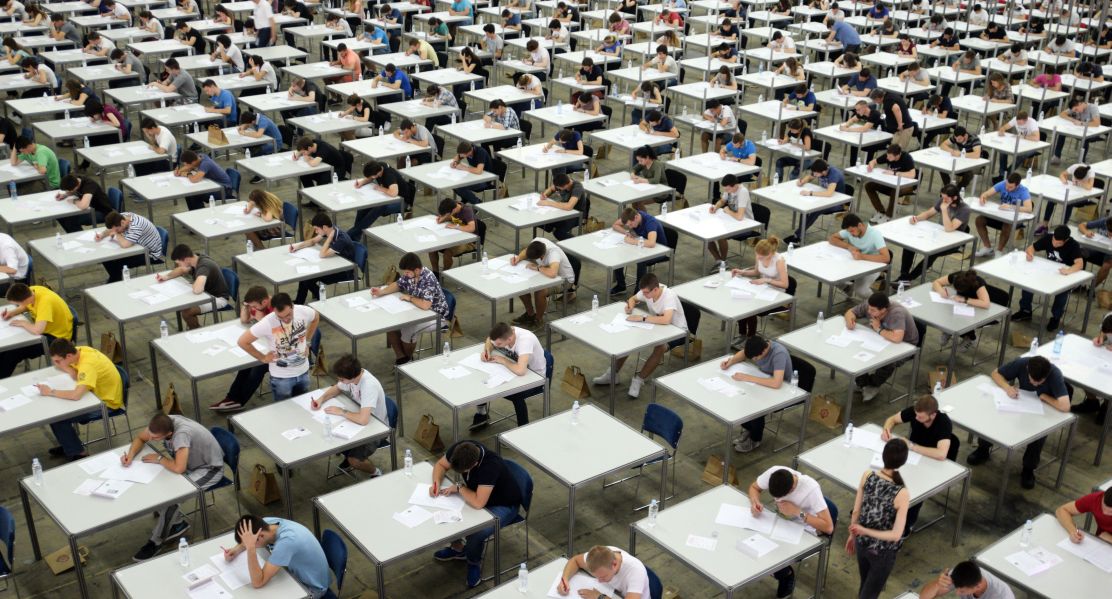

International Large Scale Assessments (ILSAs) are currently at the heart of the political economy of the education development agenda. Around 60% of countries are participating in at least one regional or international large-scale assessment. Research articles are flourishing and the media are all eyes and ears whenever new international survey results are published. However, league tables are still stirring debate in every country and opposition to exercises such as PISA is fierce, to the point that some scholars have even recommended stopping PISA altogether. Concerns about countries’ ownership and sovereignty over their own education policies are emerging and questions about methodology and robustness continue to be raised

The Sustainable Development Agenda includes the most comprehensive vision for an international education development agenda to date. It calls in its first target for countries to “ensure that all girls and boys complete free equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant effective learning outcomes” that shall be officially monitored by “the proportion of children and young people […] achieving at least a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics”, at three points in the education cycle: early grades of primary (grades 2/3), end of primary and end of lower secondary. Therefore, despite pervasive difficulties, governments and development partners have engaged in numerous ILSA initiatives, such as the Global Alliance to Monitor Learning (GAML) led by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics and Assessment for Learning (A4L), carried out by the Global Partnership for Education. It is hoped that such measures will foster sound and transparent global monitoring mechanisms that simultaneously support countries in developing their national capacity to measure and improve learning.

By many standards, however, the global education community is not there yet. The production and use of ILSAs requires improved dissemination and communication as they increasingly reach the status of global public goods. ILSAs collect a substantial amount of data on children’s learning outcomes but also background characteristics, learning environments, teachers’ characteristics and schools infrastructures. Yet the use of ILSAs as a policy tool to support national policies has not been realized and ILSAs have not been fully leveraged for global monitoring of SDG 4.

What do ILSAs enable us to measure and how is the global education community working on realizing the full potential of ILSAs?

The work around ILSAs is carried out within a fast paced environment. It is accompanied by pressing needs to develop measurement tools to support evidence-based policies, shortened business cycles and changing requirements of donor agencies. Concurrently, development actors have sought to position and legitimize themselves from the outset of this new period of global collaboration. ILSAs are thus already providing the global education community with powerful devices for advocacy and monitoring. One could cite, for instance, the widely used “250 million children failing to learn the basics” produced in 2012 by the GEMR team, the production of global and thematic monitoring indicators currently carried out by the UIS, or the GAML endeavor towards linking all regional and international assessments on a single scale either by economists or by psychometricians. They can also be used to complement analysis of other SDG 4 targets. Indeed, they are not limited to monitoring learning but broaden their reach to topics such as teachers, school infrastructures, early childhood or even equity in the allocation of educational resources.

What can’t they do? And what are the risks associated with overemphasis on ILSAs?

Despite this potential, there are also many things that are missing. Taking the half-empty glass point of view, more than 60% of low income countries do not participate in any regional or international assessment. Regional representation is also substantially undermined. Small Island Developing States (SIDS) for instance are underrepresented in global monitoring either because they do not participate in any regional or international assessment (Caribbean Islands) or because individual countries’ scores are not published (Pacific Islands). Equity measurement is also relatively weak, with only three dimensions consistently being monitored, namely gender, wealth/SES and rurality. Yet even when these dimensions are included, definitions and standards vary substantially from one assessment to another, making cross-national comparability difficult to achieve. Monitoring of children and youth with disability is also an issue, with PISA for instance allowing countries to exclude up to 5% of their target population based on rules that allow for exclusion based on disability and language. Finally, most ILSAs are school-based (a notable exception being citizen led-assessments) which de facto excludes children and youth not in school. This effectively amounts to the exclusion within the data of 42 million adolescents from middle income countries and 19 million from low income countries at the lower secondary level.

In addition, while ILSAs are no doubt attempting to grapple with the immediate needs of the global monitoring exercise, there are nevertheless pervasive risks associated with over-reliance and overemphasis on these instruments. The first has already been raised in the past; ILSAs have the potential to lose their usefulness the more they are relied upon. Indeed, increasing the stakes behind the use of ILSAs can weaken the validity and reliability of the measures derived from these data sources. ILSAs also represent a substantial drain on staff from Ministries of Education. If one includes the possibility of undertaking UNICEF’s new learning assessment module, in 2018-2019 almost 30% of all countries could undergo at least two assessments in which staff from ministries of education ought to be involved. Some countries could even have three assessments under way at any one time. Moreover, while ILSAs have beneficial effects on countries’ ability to carry out their own national assessments the number of assessment experts in developing countries remains extremely small. Consequently ILSAs could also be disruptive to the development and implementation of national learning assessments.

Including ILSAs in results frameworks of development partners also raises several issues. Until a robust and agreed upon methodology of alignment is adopted, aiming to monitor learning outcomes every other year introduces the now frequent trade-off between comparable data points and complete datasets thereby substantially weakening the usefulness and usability of a results framework. In addition, one of the main criticisms of ILSAs is the blurry line between the global public good discourse and the edu-business approach which also builds on the existence of epistemic communities, contains the expertise and instruments to a limited number of actors and maintains a certain level of information asymmetry within the education community. Should ILSAs be accepted as global public goods then it will most likely be necessary to reflect on a different global model. This model would favor both the development of national learning assessments and the capacity of countries to report at the global level with an emphasis on the former, not the latter. Solving the limited amount of knowledge transfer, developing a sustainable approach and reducing the cost of ILSAs may well require a new UN or international body to act as a global testing agency that would necessarily be neutral, public and managed by countries in such a way that would enable the development of expertise and instruments by them and for them.

Slides of the related presentation by Patrick Montjouridès during the 2017 UKFIET Conference are available here.

Other NORRAG resources about ILSAs:

- Learning from Learning Assessments: The Politics and Policies of Attaining Quality Education – Roundtable Report from event co-organised between NORRAG and Brookings’ Center for Universal Education in collaboration with PASEC (23rd June, 2016)

- PISA for Development: Expanding the Global Education Community Esperanto or Developing a Dialect? – By Camilla Addey, Humboldt University in Berlin (28th July, 2016)

- Can the Measurement of Learning Outcomes Lead to Quality Education for All? – By Pablo Zoido (former OECD), Michael Ward, Kelly Makowiecki, Lauren Miller, Catalina Covacevich (OECD) (July 21st, 2016)

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s policy or activities.