Event Report - Right to education for migrants workshop at “Education and migration” thematic day

NORRAG and RECI (Réseau Suisse Education et Coopération Internationale) organised a Thematic Day on “Education and Migration”. The event, which took place on 6 November 2018 in Bern, looked at the topic both from a Swiss and international perspective sponsors

NORRAG was specifically leading a workshop on the Right to education and migrations with Koumbou Boly-Barry, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education. Other workshops at the event discussed the following themes: What education systems have to provide to meet the needs of young refugees and asylum seekers and to ensure their right to education? What requirements must education professionals satisfy? How can previous training and certificates be recognised in a new country? And how can education contribute to help someone integrate in the society?

The workshop featured a panel discussion moderated by Joost Monks, Executive Director of NORRAG, with Koumbou Boly-Barry, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education, William Smith Senior Policy Analyst at the Global Education Monitoring Report-UNESCO and Peter Hyll-Larsen of the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE).

Right to Education actors

Koumbou Boly Barry started her remark by asking “who are the actors” in ensuring the right to education for refugees. States have a responsibility as signatories to covenants and treaties which call for the right to education. The civil society also has a responsibility to continue to take governments and states to action to fulfil their obligations. The refugees themselves are another actor, they need to organise themselves and have the motivation for education. International organisations and the community have a responsibility to provide technical support and the laws and policies to support education for migrants. The key actors are the teachers; they need to have competences and motivation to do their work.

Koumbou Boly Barry recorded a video (in French) talking about her mandate as special rapporteur:

Legal frameworks and local realities for refugee populations

William Smith, from the Global Education Monitoring Report (GEMR) presented the legal frameworks and local realities for refugee populations. The GEMR is a UNESCO initiative that monitors progress towards SDG4 and associated goals. The report also has a thematic part, which in 2019 is linked to the topic of education and migration: “Migration, displacement and education building bridges not walls”. William Smith provided the audience with the legal foundations for the right to education, which is built on two principles: equality and non-discrimination. His presentation looked at legal, structural and process factors that can deny migrant children the right to education as the implicit rights afforded by general non-discrimination (International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights[1]) and equality provisions (as mentioned in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families) can be violated in practice. Will Smith presentation also referred to the Right to Education Initiative’s background paper prepared for the 2019 Global Education Monitoring Report as a starting point for his presentation. The background paper provides a breakdown of states international commitment on the right to education by looking at whether or not states have ratified the legal conventions that apply to education of migrants and refugees. Only 31 countries have ratified the six treaties concerned with the right to education for migrant and refugees including: the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC), the UNESCO Convention against Discrimination in Education (CADE) and the treaties specific to migrants and refugees: Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (CSR), the Protocol to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees (PCSR) and the International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families (ICRMW).

National legislations also might lag behind in affording the right to education for populations that are the most vulnerable, such as refugees, even for those nations that have ratified the international conventions. Slovenia and Uganda are positive examples which extend the right to education to stateless persons (Slovenia) or Internally Displaced Persons (Uganda). Even if there is a strong legal framework, other structural barriers to enrolments may exist such as language issues, lack of documentation, school fees, requirements for identity documents to enrollment or difficulties in recognizing the child’s prior learning.

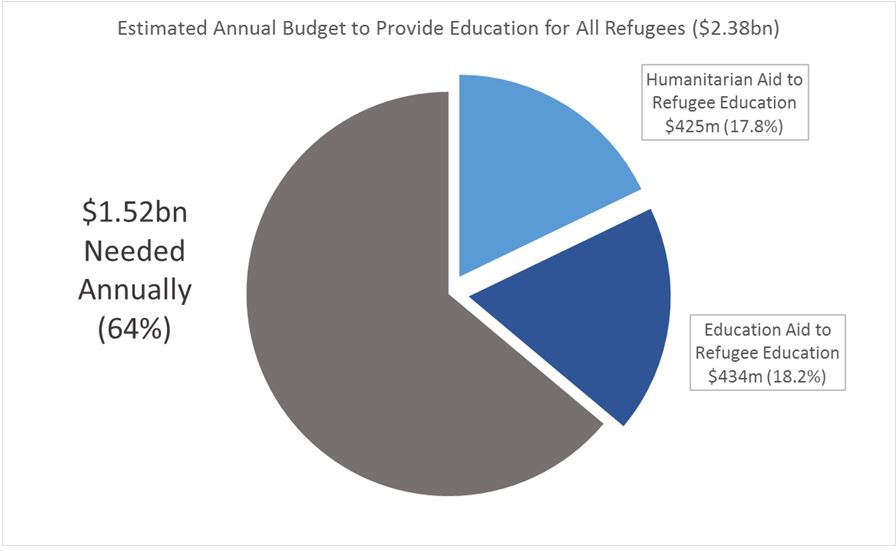

Regarding financing refugee education, Save the Children has estimated the financial needs to ensure that refugee children receive education within five months of their arrival in host countries to US$21.5bn over the next five years, with US$11.9bn financed by the international community. Although there has been a steady increase from 2014 to 2016 in both humanitarian aid and education aid going to refugee education through projects and direct funding in the countries members of the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), there is still a funding gap of 64 per cent (US$1.52bn) needed annually to provide education for all refugees.

In addition, there is a funding imbalance with a lot of the money needed going to Syria with the effect that other refugee crises are seriously underfunded. For instance only 2 per cent of the funding needs have been secured for the provision of education for South Sudanese refugees in Uganda.

To ensure the Right to education for refugees, country commitment is needed at all levels, additionally, the removal of local barriers to the right to education should be lifted, increased accountability mechanism should be put in place and better funding through increased commitment to financing refugee education.

Meeting the right to education in emergency and situation of crisis through standards and coordination

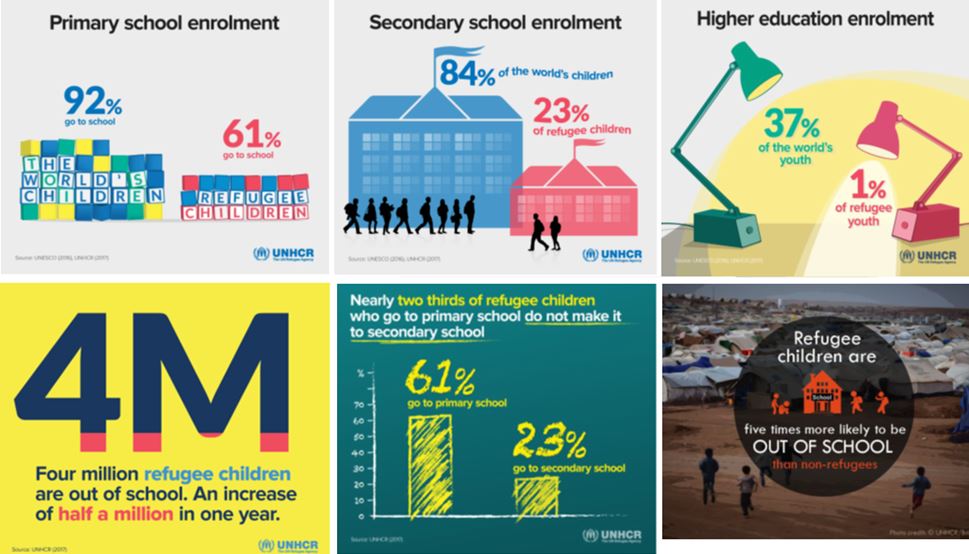

Peter Hyll-Larsen is the coordinator for advocacy at the Inter-Agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE) which is an international network with about fifteen thousand members from the UN agencies, international NGOs, donors, governmental personnel and academics. He started his presentation by addressing the needed improvement in refugee’s education enrolment. For example, enrolment in primary education is now 92% for the world’s children, but only 61% for refugee populations. For secondary education, the percentages are 84% for the world’s children in comparison to 23% for refugees, and for higher education it is only 1% compared to 37% for the world’s youth in general. Hence, the major challenge lies not just in primary enrolment any longer, but much more in closing the massive drop in retention and enrolment into secondary education – and thus to serve refugee children’s right throughout the span of a childhood, adolescence and youth, up until the age of 18 and beyond.

What legal framework applies for the right to education in situations of emergencies and crisis and how can they help us address this need to focus on secondary education? Peter Hyll-Larsen looked at how the right to education is affirmed at all levels of legislation, such as national constitution and laws, regional conventions, the international body of human rights and humanitarian law, which includes both the 1951 Convention on Refugees and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). In comparing the latter two conventions, Peter Hyll-Larsen demonstrated that the CRC actually offers much better refugee education protection from early childhood to higher education (in articles 2, 22, 28, 29 and 38 in particular), than the older 1951 Convention, that only really looks at basic education and not the whole span of a child’s educational rights and needs, from 0 to 18 years and beyond. We should therefore as a community be better at using the CRC, and other key human rights instruments, in our refugee responses and in advocating for the right to education that is in the best interest of all children and youth.

However, the political realities have changed and the nature and scope of violations has changed dramatically as a result. For example, the numbers of refugees keep increasing and there are direct and intentional attacks on human rights and education, such as the targeting of schools in Nigeria or Syria. Hence, in addition to the attack on human rights and education, the adherence to International Humanitarian Law, International Human Rights Law and Refugee Law itself is under attack. The response needs to be two-pronged: both better awareness and adherence to the human rights framework, as well as a greater emphasis on the SDGs, that are more political in nature and therefore perhaps not seen as so contentious.

Therefore, Peter Hyll-Larsen urged that there is a serious need to find new solutions to uphold the right to education for refugees, stateless and internally displaced persons – and linking education in emergencies to the wider SDG framework is one of them. He affirmed that there are promising efforts underway for protecting refugees at the international level, such as UNHCR’s Alternative to Camps policy, which is a push for inclusion in national sector planning and national education systems and where a country like Uganda is leading the way with impressive new policies. However, the process and the beautiful policies need to be followed up by national legislation and commitment and by effective national and international budget allocations and strong monitoring frameworks.

Panel discussion

The panel discussion started with a question on how to move forward to find new solutions for the Right to Education for refugees, especially that the current number of refugees is twenty-five million people and it is still growing. On trying to find a vision for the future, the panelists emphasized the importance of using the current legal systems as tools to fight for the right to education for refugees. Creativity and innovations are also important avenues but one should be cautious with ICT, innovative solutions should really serve the benefit of education and not be a channel for private actors to try their technology.

New data and new information is needed in order to be able to craft innovative solutions and approaches for the problem. However, one challenge that is yet to be solved is the gap between academia and real life, since peer reviewed research papers take a long time to have a real impact on the ground. The panelists stressed the need to shorten this gap so that refugees can benefit faster from the research conducted, one model is here ‘action research’. Hence, more training is needed to give support for capacity builders. Another important challenge when it comes to research is that published reports have to be timely and evidence-based, while changes are happening fast on the ground. Consequently, it was mentioned that the whole research structure needs to be adjusted and there should be open access research.

Moreover, the panelists discussed the need to find ways to hold the governments accountable. In addition to providing assistance to refugees, the international community, through the office of the special rapporteur to the right to education and other channels, need to keep the pressure on governments to avoid or rectify any human rights violations. On the ground level, the panelists described the need to raise awareness and educate people in host countries to be more hospitable towards the refugees. There is a growing public discourse against refugees nowadays, where some citizens of the host countries think the quality of education is being compromised because of the growing number of immigrants and refugees in their country. To counter this narrative, we need to have organisations and people who champion the right to education of refugees and migrants. However, it is important to note that some countries do not have the resources to support the refugees, since they are already facing challenges and obstacles to develop their education systems. This makes the crisis more problematic.

In the end, it was agreed among all panelists that education is the key towards finding new creative solutions. Educated individuals are more welcoming and have less negative attitude towards migrants and refugees. It is also the quality of education, about what to teach and how to develop critical thinking to be able to counter the narratives of populists or demagogues spreading a negative message of refugees. Hence, the right to education for refugees should be guaranteed through providing access to good quality education for all.

Concluding the panel, it was reminded that migration is not a new phenomenon. We need to continue to push for education in emergencies with the help of the special rapporteur. At the international level, we already made the case that education in emergencies is a necessity, with the creation of the Global Education Cluster. We also need to bring all the responsible actors to play their role and meet their responsibilities: organization, international communities, researchers and the private sector and develop appropriate levels of accountability at all levels.

Download the full report (in German) for more information on the thematic day “Education and Migration”, and on the other stimulating sessions of this event including:

- What education systems have to provide to meet the needs of young refugees and asylum seekers and to ensure their right to education?

- What requirements must education professionals satisfy?

- How can previous training and certificates be recognised in a new country?

- And how can education contribute to help someone integrate in the society?

Final report of the event (in German) (in French) – please note that the Right to Education workshop is in English

More information: Programme (French) Programm (German). Description of the Workshops (French / German)

More information: https://goo.gl/tgs8jf

[1] CESCR General Comment No. 13: The Right to Education (Art. 13)