Structuring Democratic Voice to Improve Accountability in Education

This NORRAG Highlights is contributed by William C. Smith, University of Edinburgh, and Aaron Benavot, University at Albany-SUNY. In this post, the last of a three-part series, the authors discuss the importance of providing structured space for democratic deliberation in the policy making and evaluation process. In contrast to test-based accountability and other forms of externally imposed accountability, including structured democratic voice can improve trust in the system and the teaching profession, while increasing the likelihood the large collective aims of education are met.

Test-based accountability has been gaining momentum globally as the preferred approach to holding teachers and schools accountable for student achievement. Ultimately, however, this approach, which has gained the enthusiastic support of powerful actors, is doomed to fail. Opposition groups — teachers, principals, parents — are raising their voices to disestablish a system of accountability in which they have no voice.

The first blog in this series highlighted the unfulfilled assumptions which are axiomatically contradictory to the broader aims of education. The second blog illustrated several of the negative outcomes that eventuate when a testing culture consumes teacher appraisals and school workplaces. It argued that the potential benefits of appraising teaching are being undermined by test-based accountability. Appraisal feedback is increasingly seen as an automated, administrative task of little value to improve teaching. Teachers’ job satisfaction in such a test-obsessed environment is diminished.

Not surprisingly, test-based accountability has found limited support among the educators being judged. Having had little to say about the nature of the accountability policy put into place, or the process by which it was implemented, most educators view such accountability systems as an oppressive, external force that stymies creativity, energy and enthusiasm in teaching. And although externally mandated accountability systems are not limited to test-based accountability, all such approaches tend to be associated with feelings of helplessness and confusion by those being evaluated.

This blog series ends with a hint of optimism. Test-based and externally driven forms of accountability, while predominant, are not the only approaches to be considered. There are alternatives. What happens when educational goals and accountability approaches are discussed in earnest by a larger community of stakeholders? When happens when decisions reflect a broader consensus among diverse interested parties? What happens when interlocutors prioritize trust in the process and when those on the front line of implementation feel their concerns have been heard and considered?

Structured Democratic Voice

We recently suggested that structured democratic voice has an important role to play in improving accountability in education. In essence, structured democratic voice is the creation of space during the policy planning and evaluation processes for teachers, parents, students, and other community members to express their concerns, in ways that are valued. Structured democratic voice can include either direct – such as the mass participation in municipal, state, and national conferences on education policy in Brazil – or representative democratic voice – such as teacher representation on the central education board in Uruguay – and recognizes that “accountability actions are part of a broader and longer process of engagement between actors and the state” (Dewachter et al., 2018, p. 168).

Critically, structured democratic voice increases trust among actors in the system. Done properly, it signals to educators that their professional expertise is valued and seriously considered. Collaborative processes based on active consultation and participation elicit more trust in part due to the increased faith teachers and other educators have that the co-constructed policy is fair and just.

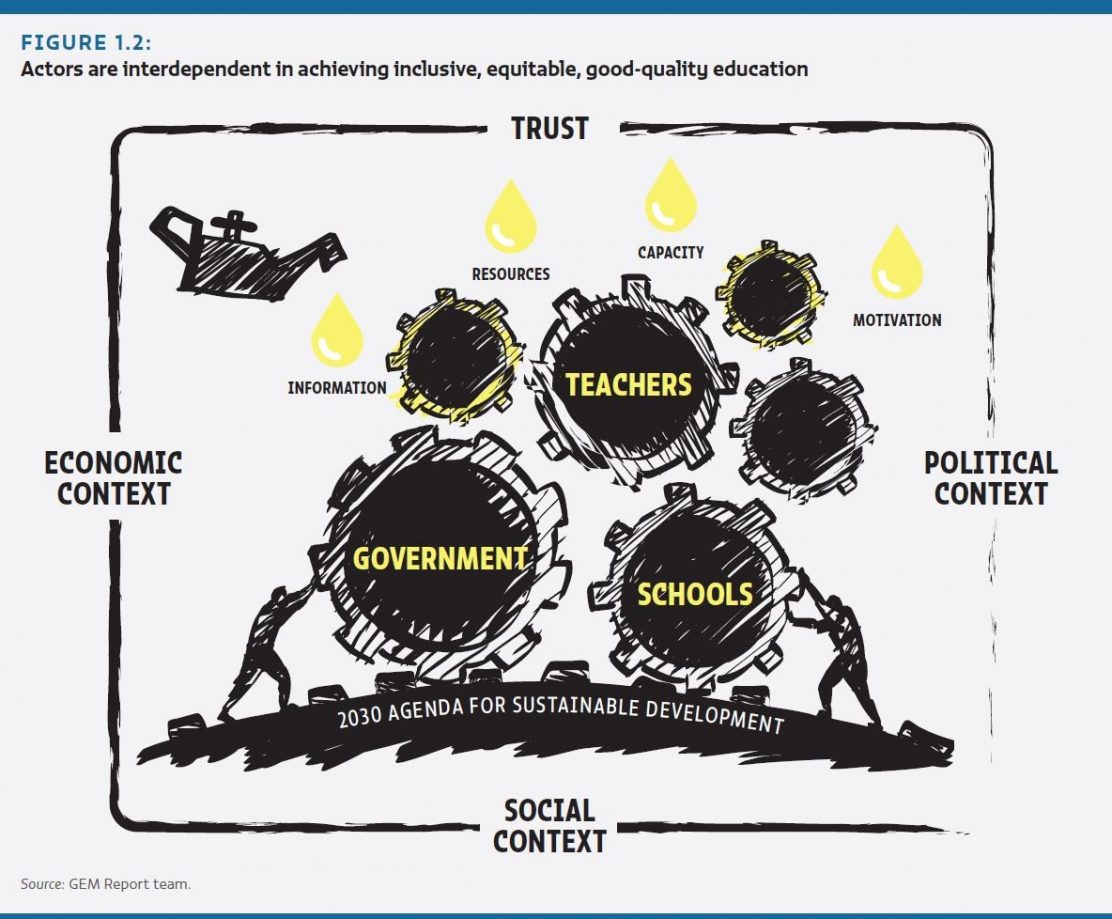

Trust is an essential feature in any accountability system. The 2017/18 Global Education Monitoring Report highlighted trust as a contextual element that shapes how accountability if felt and which approach to accountability is likely to be implemented. In addition to trust, the figure below identifies four aspects of the enabling environment – resources, capacity, motivation and information (represented by oil drops) – which influence the effectiveness of an accountability approach, once in place.

Source: UNESCO

Beyond trust, structured democratic voice can strengthen the enabling environment. It increases motivation and support of the accountability approach since actors have contributed to its creation. Structured democratic voice also improves information among all actors by clarifying respective roles and reducing misunderstanding. Individuals are then more likely to accurately understand and report on their work.

Lessons from Implementing Structured Democratic Voice

Viewing the policymaking and evaluation space as collaborative space, beyond the sole proprietorship of government, is relatively new. Still, early attempts at implementation point to key lessons. During the Marcelo Ebrand administration (2006-2012) the Mexico City government organized multiple points for public participation as it sought to become the most environmentally sustainable city in Latin America. The ambitious, 15 year Green Plan included a pre-launch consultation and post-launch oversight board. Structured and led largely by the government, below expected levels of participation highlight the importance of engaging through multiple mediums. Communicating primarily through online surveys and forums limited the potential of structured democratic voice to the 30% of the population that had internet access in 2010, limiting public representation, especially among the most marginalized. While the oversight board did meet in person there were questions about the quality and accessibility of documents, which were shared with the public through a website.

By contrast, Malawi community meetings have occasionally led to the collective identification and amelioration of issues. In a rural community near Zomba, community leaders, together with parents, students, civil society organizations, and local government officials recognized the role child marriage was playing in female completion and dropout rates. With regulations already in place and child marriage illegal throughout the country, relying on the rule of law was not an option. Instead, participants laid out a collective plan which outlined individual actor responsibilities. Penalties were also jointly decided. Village leaders who allowed early marriage were to be removed from their position by the senior chief and parents who permitted their child to marry early would also face consequences. The collective efforts led to a reduction in female dropout rates and the return of 74 married girls to school.

These and other examples suggest it is important to consider who is structuring the democratic voice, whether it is seen as genuine, and how it is implemented. Bringing multiple, sometimes divergent, views together in a single discussion platform is never easy. The challenges facing those attempting to implement structured democratic voice are many. Pagatpatan and Ward (2017) focused on public participation in health policy and highlighted four potential obstacles: partnership synergy, inclusiveness, deliberativeness, and political commitment.

Partnership synergy can be challenging to attain, especially given the time required to build trust among diverse stakeholders. As demonstrated in the above example of community meetings in Malawi, having a shared aim or emphasizing a shared identity can facilitate synergy. Formal inclusion in the conversation does not necessarily mean that the actor’s voice is heard or valued. Joint sector reviews are ambitious efforts by the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) to bring together government agencies, civil society, donors, and other education stakeholders and facilitate mutual accountability. An evaluation of 39 reviews from 2014-2015 found that without a clear role, civil society often took a back seat in conversations, often resulting in binary conversations between the government and donor.

Processes that are not deliberate have uneven or poor quality dialogue. In the attempt to introduce structured democratic voice in evaluating the 15 year Green Plan in Mexico City, complaints from board and community members that necessary information was unavailable and/or inaccurate led to high board turnover, undermining stability and effectiveness.

Political commitment or political will goes beyond providing space for voice to allocating resources to ensure the agreed upon plans are sustainable. In Wolaita Zone, Ethiopia, Link Community Development (LCD) worked with the local government to increase participation in the local school meeting while increasing the capacity of authorities through training on an integrated information system. While the meetings were a success and the schools agreed to continue them beyond the involvement of LCD, an independent project summary report questioned whether the government was committed to long term funding for the meetings – despite the benefits they received.

Governments unfamiliar or opposed to public participation are less likely to incorporate space for democratic voice. In such contexts it is useful to identify a policy topic more open to public comment that can demonstrate the benefits of democratic voice. For example, some East Asian countries practice what some call ‘soft authoritarianism’ – providing opportunities for public engagement in targeted areas, such as economic growth. Chou and Huque (2016) suggest this may lead to an expanded, virtuous cycles with other subject areas becoming increasingly open to public input and engagement.

A Process Worth Pursuing

Despite the aforementioned challenges in sustaining structured democratic voice in education, it is a process worth pursuing. Externally-driven, results-oriented accountability have undermined trust and done little to improve learning or reduce disparities. Structured democratic voice is a key ingredient to improved accountability approaches. Structuring collaborative spaces for increased voice in policy making and evaluation process helps align the aims of key actors, and increases their vested interest in the policy’s success. Given its longer-term horizon, it can provide stability as political and economic circumstances change. Finally, structured democratic voice helps articulate collective goals for education and increases the likelihood that they will be met.

Acknowledgements:

This blog draws significantly from the following recently published article

Smith, W.C. & Benavot, A. (2019). Improving accountability in education: the importance of structured democratic voice. Asia Pacific Education Review, 20, 193-205.

About the authors:

William C. Smith is a Senior Lecturer in Education and International Development and pathway coordinator for the MSc in Comparative Education and International Development programme at the University of Edinburgh. He was previously a Senior Policy Analyst for UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report. His publications on education policy and international development include his edited book The Global Testing Culture: Shaping Education Policy, Perceptions, and Practice (2016, Symposium Books). Email: w.smith@ed.ac.uk

Aaron Benavot is Professor of Global Education Policy in the School of Education at the University at Albany-SUNY with interests in comparative education research and international education policies. In 2018 he served as a Fulbright Specialist in Viet Nam and in 2019 as a High-Level Expert in lifelong learning at the East China Normal University in Shanghai, China. During 2014-2017, Aaron was Director of UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring Report, an independent, evidence-based annual report, which analyzes progress towards international education targets in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. He recently co-led a 10 country study exploring the mainstreaming of education for global citizenship and sustainable development in policies and curricula (UNESCO, forthcoming). He is also a co-convener of NISSEM (nissem.org), which recently published a special volume entitled: NISSEM Global Briefs: Educating for the social, the emotional and the sustainable.

Editor’s Note: This post is the concluding essay for a three-part mini-series of posts that discuss issues pertinent to the global growth of accountability systems in education, its relevance to stakeholders and the challenges moving forward. Part I of the mini-series delves into the discourse around accountability as solution to the learning crisis worldwide; Part II examines teachers’ perspective to testing and accountability, and finally, Part III sums up the importance of multi-stakeholder structures in education policy-making and evaluation.

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities.