TINA comes to European Education? The European Commission, PISA, PIAAC, and American-Style Knowledge Capital Theory

This NORRAG Highlights is contributed by Hikaru Komatsu (Associate Professor at National Taiwan University) and Jeremy Rappleye (Associate Professor at Kyoto University, Graduate School of Education). The authors critically analyzed the European Commission (EC) report by Hanushek and Woessmann and refute their human/knowledge capital claims. Contrary to the EC report, their findings indicate that there is no correlation between PISA scores/ PIAAC scores and economic growth.

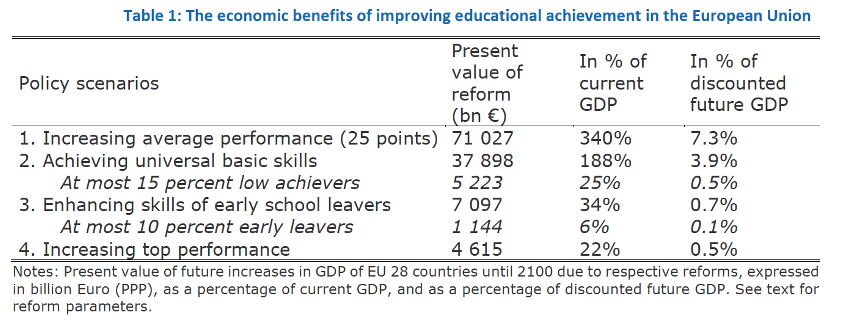

In September 2019 the European Commission (EC) published The Economic Benefits of Improving Educational Achievement in the European Union: An Update and Extension. It claims to lay out the impressive economic benefits of improving PISA scores across the European Union, as shown in Table 1. It contends that more focused policy work on improving PISA scores in core subjects for 15-year olds will later improve the skills of the future EU workforce, and this adult skills ‘boost’ will eventually lead to greater economic growth. We sketch this causal sequence in Figure 1.

Table 1. Economic Benefits of Improving Educational Attainment (EU, 2019, p.5)

Figure 1. Potential impacts of improved students’ test scores (i.e., cognitive skills) on the skills of workforce and then economic growth.

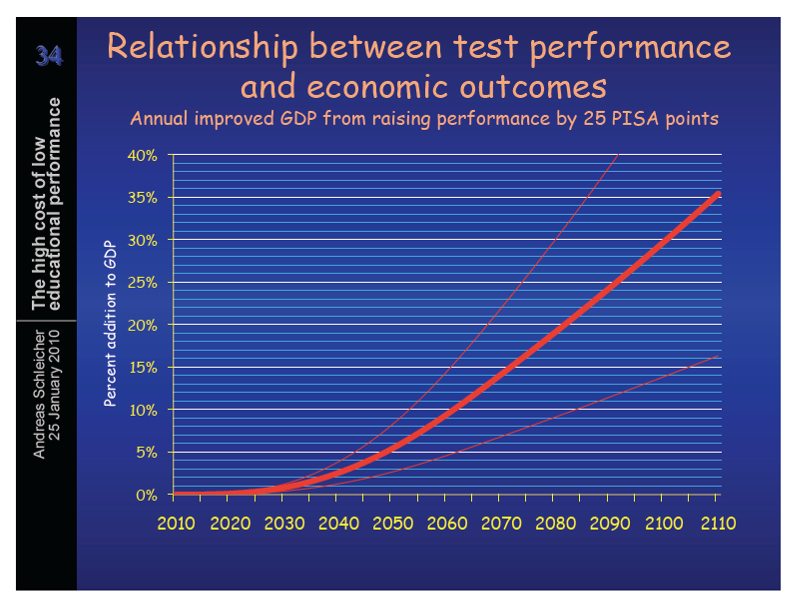

The EC report was written by Eric Hanushek (Hoover Institute, a think tank on the campus of Stanford University) and Ludger Woessmann (University of Munich, ifo Center for Economics of Education). It laid out the same findings, methods and arguments that can be found in a range of publications in the United States dating back to the early 2000s (e.g., Hanushek & Kimiko, 2000), and reaching back even – with a bit more historical awareness – to the heady Anglo-American neo-liberalism of Reagan and Thatcher in the 1980s (e.g., Hanushek, 1981, Hanushek, 1986). These claims were articulated strongly in a 2013 book by the same authors, published by the Brookings Institute and intended to reach US policymakers, entitled Endangering Prosperity: A Global Look at the American School. These same findings were also publicized in major reports by the World Bank (2007) and the OECD (2010, 2015), both of which commissioned Hanushek and Woessmann to write their findings into development policy. The World Bank would later officially adopt the model as the underpinning logic of Learning for All (2011) (see Auld, Morris, and Rappleye, 2019), while the OECD’s 2010 report entitled The High Cost of Low Educational Performance – The Long-Run Impacts of Improving PISA Outcomes would be virtually transferred carbon copy into the EC’s 2019 report. That is, the EC 2019 Report claims that an aggressive, focused 15-20 year reform push to raise scores by 25-points would “add €71 trillion to EU GDP over the status quo” and which “amounts to an aggregate EU gain of almost 3 times current levels of GDP and an average GDP that is seven percent higher for the remainder of the century”. Based on the Hanushek and Woessmann numbers, Andreas Schleicher enticed European leaders with precisely that same narrative in 2010, as shown here in a slide from his presentation below (Slide 34 in the original presentation). Schleicher claimed that a PISA-improvement reform add 30% of the current GDP in 2100, which makes the total economic value of this reform is equivalent to 340% of the current GDP – the exact value shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Andreas Schleicher’s January 2010 presentation to EU leaders

Interestingly, in the same presentation Schleicher-voicing-Hanushek even goes so far as to boldly claim that the “estimated relationship is little affected by including other possible determinants of economic growth” (e.g. geographic location, political stability, population growth, school inputs such as pupil-student teacher ratios and spending) (Slide 41). In fact, the only factor that seems to matter despite the cognitive skills of 15-year olds is the liberalization of the economy (i.e. a closed economy could reduce the possible gains). Viewed historically, the 2019 EU Report must be seen then as the movement of American-made Knowledge Capital theory, rooted in the Anglo-American context of the 1980s, first into PISA (and the World Bank), then into the EU’s flagship policy work on education. We might expect this of a “developing” country under donor aid tied conditionality, but what are we to make of the EC adopting all of this voluntarily?

For quite some time, we and others (here, here, here, and here) have pointed out that the Hanushek and Woessmann “findings” are deeply flawed. Our work includes a number of published papers, newspaper articles, and blogs published since 2016. We have tried to call attention to this situation in two previous NORRAG blog pieces here and here. Our argument in the main 2017 paper was simple. Hanushek and Woessmann used a relationship between students’ performance in international tests and economic growth for estimating the economic value of improving 25 points of PISA scores. However, Hanushek and Woessmann surprisingly compared students’ performance for a given period and economic growth for the same period. However, as it logically takes several decades for that cohort of students to occupy a major portion of workforce and then contribute to economic growth. We logically compared students’ performance for a given period and economic growth for a subsequent period. Surprisingly, in doing so we discovered virtually no relationship between them, casting strong doubts on the purportedly strong causal claims (Komatsu & Rappleye, 2017). While we find it disheartening that there has been no response to our work, it is far more disappointing that find that now the EC have turned to Hanushek and Woessmann, paying them hefty consultancy fees to write policy recommendations for Europe. We wonder aloud: Why does the EC Directorate for Education, Youth, Sport, and Culture needs to turn to American think tanks to generate new policy ideas?

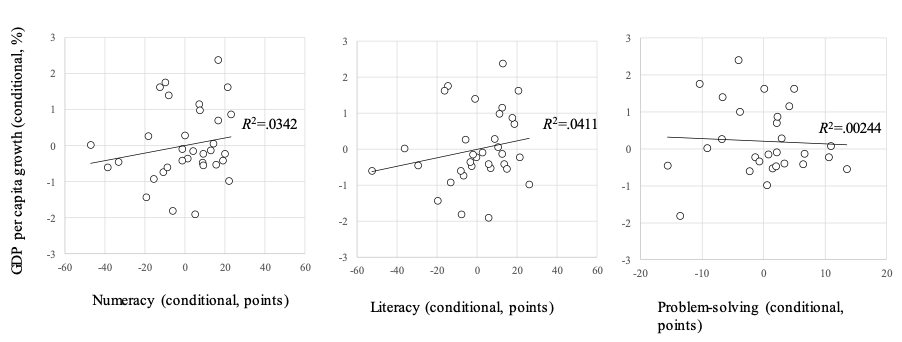

We wish to again confirm – empirically – that the Hanushek and Woessmann numbers are indeed flawed. In fact, since 2016 our analytical work has not stopped. In our most recent paper, we attempted to test the Knowledge Capital claims of Hanushek and Woessmann in a more direct, robust way: not through PISA but through PIAAC data. In fact, the PIAAC data has a distinct advantage over that of PISA because it measures skills (numeracy, literacy, and problem-solving abilities) across the entire workforce (age 15-65). This means that the skills of the labor force can be compared with economic growth without needing to account for the time lag (recall Figure 1). What emerges when we use PIAAC? Figure 3 shows the results.

Figure 3. Relationship between PIAAC scores and economic growth (Rappleye and Komatsu, 2019)

In simple terms, this means that there is virtually no relationship between PIAAC and economic growth, certainly nothing remotely approaching the GDP growth projected by Hanushek and Woessmann in the 2019 EC Report. PIAAC scores explained – at best – a mere 4% or less of the between-country variations in GDP per capita growth.

Returning again to the larger picture, it seems that now the EU and OECD, alongside the World Bank, OECD and often highly influential figures in UNESCO, are now utilizing the same Hanushek and Woessmann Knowledge Capital claims. What makes this ‘Western consensus’ so alarming – at least to us – is not simply that education and economics are being so tightly coupled or that PISA is being embedded deeply into policymaking goals through these works. It is, instead, that so many leading minds in the West seem unable or unwilling to think differently.

Are there no alternatives left anymore? For a tradition as rich and diverse as Europe to join the OECD and World Bank in promoting neo-liberal US think tank recommendations for education seems to suggest that Margaret Thatcher was indeed right: There is No Alternative. Perhaps the only substantial work left to be done, by Europeans and Americans at least, is to expand this narrative and PISA to the rest of the World, a trend we find accelerating worldwide as PISA is now anchored in the SDGs.

More optimistically, perhaps it is time now to look beyond both Europe and America altogether. There are, indeed, alternatives (i.e., others) but the best Western minds seem strangely unable to recognize them at present. There are nations that have scored consistently high in cross-national surveys using vastly different policy and practice approaches, but unfortunately – at least for the TINA faithful – the experience of these countries only serve to refute the human/knowledge capital claims. Still, what is encouraging here is that most of those same countries have – even when facing stagnant economic growth – neither embraced the advice of American think tanks nor veered away from the primary commitment of using education to serve social and cultural goals.

About the Authors: Hikaru Komatsu is an Associate Professor at National Taiwan University. His recent work has focused on the relationship between culture, education, and sustainability. Jeremy Rappleye is an Associate Professor at Kyoto University, Graduate School of Education. His work spotlights the genealogy and problems inherent in the new global education narrative promoted by the OECD and World Bank.

Authors’ Note: Both authors contributed equally to this piece.

Contribute: The NORRAG Blog provides a platform for debate and ideas exchange for education stakeholders. Therefore, if you would like to contribute to the discussion by writing your own blog post please visit our dedicated contribute page for detailed instructions on how to submit.

Disclaimer: NORRAG’s blog offers a space for dialogue about issues, research and opinion on education and development. The views and factual claims made in NORRAG posts are the responsibility of their authors and are not necessarily representative of NORRAG’s opinion, policy or activities

Hanushek and Woessman’s statistical analyses are totally incorrect and dangerous., as above and as I elaborated in the reference below. Their specification of what economists call an aggregate production function (i.e., one with GDP as the dependent variable) was completely idiosyncratic and different specifications would show that PISA scores are irrelevant to economic growth. Social science has no ability to answer the broader question of how much education “quality” contributes to GDP now, let alone forecast it 80 years into the future as they did. This is simply absurd. Common sense tells us that it is impossible to separate one factor from the myriad factors that affect GDP. It is understandable why education advocates latch on to anything that will further their important case for investment in education, but this form of crystal-ball gazing needs to be completely repudiated.

Steven Klees, University of Maryland

“Inferences from Regression Analysis: Are They Valid?” Real World Economics Review, April 2016, 74, 85-97

Hanushek and Woessman’s statistical analyses are totally incorrect and dangerous., as above and as I elaborated in the reference below. Their specification of what economists call an aggregate production function (i.e., one with GDP as the dependent variable) was completely idiosyncratic and different specifications would show that PISA scores are irrelevant to economic growth. Social science has no ability to answer the broader question of how much education “quality” contributes to GDP now, let alone forecast it 80 years into the future as they did. This is simply absurd. Common sense tells us that it is impossible to separate one factor from the myriad factors that affect GDP. It is understandable why education advocates latch on to anything that will further their important case for investment in education, but this form of crystal-ball gazing needs to be completely repudiated.

Steven Klees, University of Maryland

“Inferences from Regression Analysis: Are They Valid?” Real World Economics Review, April 2016, 74, 85-97