Work-based Learning in Kyrgyz TVET Colleges

In this blogpost, Janyl Bokonbaeva reports on opportunites and challenges in the implementation of work-based learning programmes in Kyrgyz TVET colleges.

Work-based Learning (WBL) is an approach in TVET known to foster better employability, boost education quality and overall economic growth. Since late 2021, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) has piloted WBL in eight Kyrgyz TVET colleges by developing and monitoring WBL programs based on occupational standards. Sixteen secondary TVET specializations (equivalent to level 5 of the National Qualification Framework) were supported in the framework of the ADB project’s “Sector Development Program: Skills for Inclusive Growth” WBL intervention.1 These specializations ranged from electricians, veterinarian paramedics and car locksmiths to fashion designers, construction technicians and masters of industrial training. With the piloting nearing its end, all eight colleges filled out a self-evaluation report highlighting successes and lessons learnt from the WBL test implementation.

Training and Curricula: Traditional practice-oriented training in Kyrgyz colleges is a so-called “practice” (“praktika” in Russian, or “praktikalyk sabak” in Kyrgyz). This learning can be a basic, introductory practice for first year students, or a more advanced production-based practice or the “pre-qualification” one – all duly reflected in normative documents. WBL, as an umbrella term, stands for a more holistic understanding of all workplace activities that involve training in real-life professional contexts. Namely, WBL in pilot colleges now comprises a range of practice-oriented learning and training components, such as excursions to production areas, practical classes in workshops, laboratories, guest lectures by company leaders, various festivals, competitions and study projects, etc. One example is a “Sketch Day” in a local museum, where college students draw inspiration from the world of art for their studies in design. Colleges’ formal regulations, curricula and timetables reflect these WBL options, which makes these documents and instruments easy to use and transparent for teachers and students. What is the benefit of that? Including WBL in study curricula, student guidebooks and timetables allows to immediately see what topics will be studied at a given time at a given workplace, as well as how many hours that will take. By means of scaling out, one of the colleges went beyond pilot specializations and included WBL in study documents and provisions for all other specializations as well.

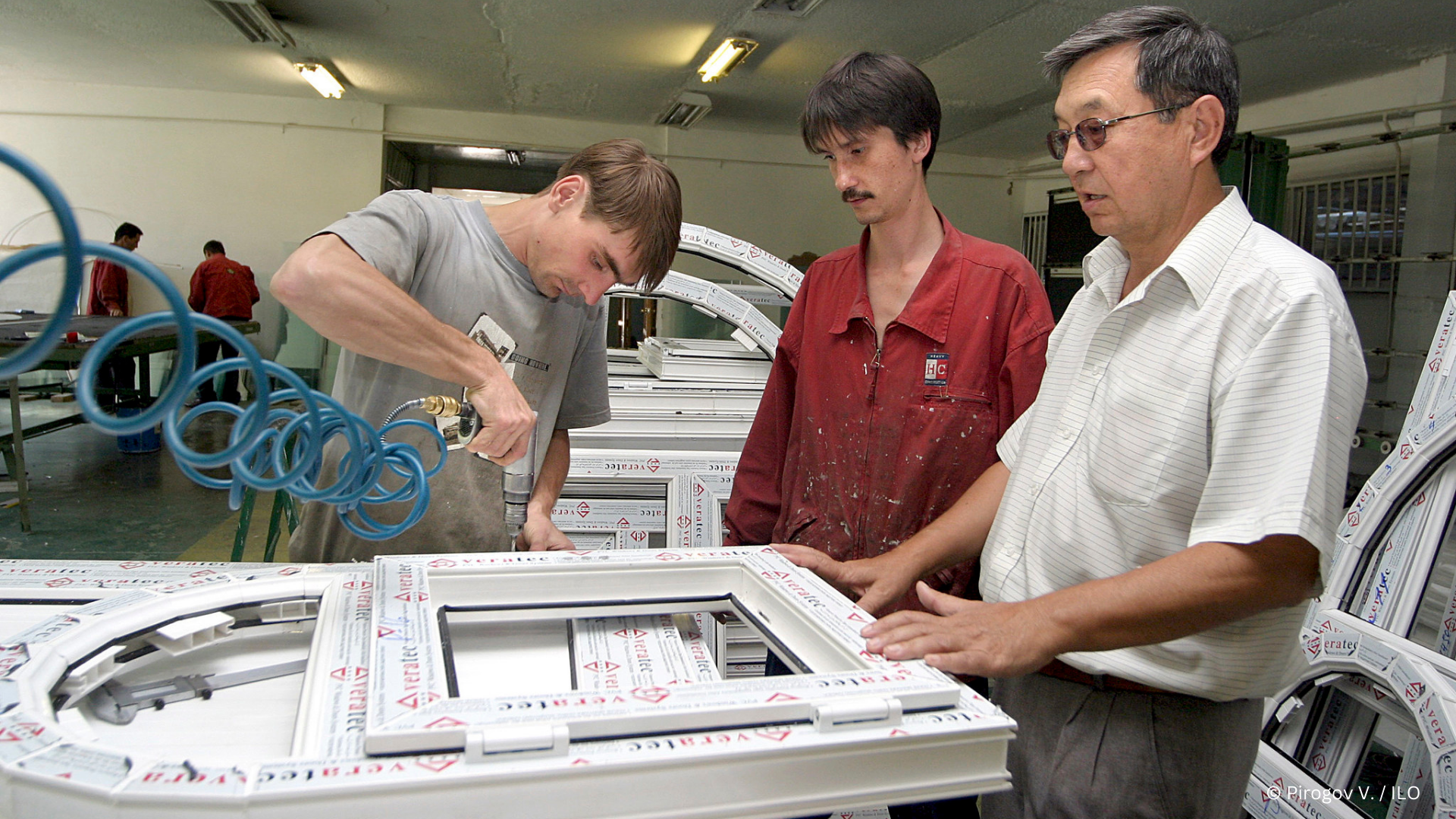

Industry partnership: Hiring company specialists as part-time teachers is yet another WBL approach aiming at better acquisition of professional competencies by students. While low salaries in public colleges remain an obstacle for attracting more industry professionals, college directors are generally successful at promoting engagement in teaching as a form of “giving back” and social responsibility among industry people. These part-time teachers play a key role in gaining and securing access for students to workplaces in companies and factories, thus further strengthening the WBL approach.

Yet private sector cooperation is not always a straightforward road. Due to high demand in tailors and growing trade volumes, local employers tend to overlook the clothing design and modelling component in students’ training plans. Instead, they prefer that students spend more time sewing rather than drawing and modelling. This downgrades students’ qualification and weakens their professional motivation. In this regard, colleges spend a lot of effort in negotiating with employers to correct the situation. The students’ voice has been strengthened in recent years; in self-governing bodies, such as the Student Council or Student Parliament, students formulate their learning expectations and advocate for their grievances with the employers. Student activism is vital when it comes to strengthening career guidance, linkages with the job market and professional development of young technicians.

Not all private sector actors are willing to accept students into their workplaces, even for short periods. Nor are all entrepreneurs willing to visit colleges with master classes or presentations. Sustaining a continuous dialogue seems the best way to build relationships with the industry; the

colleges should keep attuning their study programs, content and strategic planning to industry needs and demands.

Engaging and empowering teachers and masters in colleges: As is often the case with new initiatives, WBL implementation met with some (albeit tacit) resistance and misunderstandings from teachers. Many educators have spent most of their professional career in the traditional realm of “praktika”, and had difficulties accepting the larger, universal notion of WBL. However, the initial resistance subsided once the teachers got more familiar with WBL via project capacity building. Moreover, a teacher underlined that WBL, as opposed to traditional “praktika”, gives a “clearer picture of what a student learns, as the theory is immediately explored during practical classes” and is therefore a “more promising kind of study program”. Another college representative also confirmed that WBL’s most useful features are the focus on competencies and hands-on training after each classroom module.

Student participation: First year students are 16 to 18 years old when they enter TVET, which means they still need support in job orientation and soft skills development. Likewise, the students of the first year of study are mostly preoccupied with continuing – and finishing – their secondary level school education, which TVET colleges provide. All this leads to gaps in students’ knowledge and motivation for their future profession. Yet, the level of knowledge and personal interest rises drastically right after the first WBL experience. After a hands-on encounter with their working place, after listening to guest lectures by company officials and participating in company visits, students report higher motivation levels. Colleges that saw this happening amended their study programs by, for example, introducing a new course “Introduction into profession” for the 1 st year students. This class deals with what students’ profession of choice looks like, what is special about it –- but also what risks and challenges one should be aware of when practicing it.

Introducing new technologies in teaching and assessment: To keep up with the rapid technology developments, Kyrgyz TVET faces a daunting task of providing students with a high-quality learning environment. This is a big challenge for a country with low TVET funding and chronic financial difficulties. To counter this, the project “Sector Development Program: Skills for Inclusive Growth” provided modern training equipment and facilities for the pilot colleges. For instance, the project furnished a test laboratory for construction materials for the Bishkek College of Architecture and Construction Management. This facility serves four WBL- related purposes: student training, teacher professional development, profit making/private sector cooperation but also assessment based on relevant professional standards and carried out jointly with industry representatives.

Outlook:

Further WBL implementation and scaling out for Kyrgyz colleges will happen along the following lines:

– Social partnership. Colleges should carry on fostering cooperation with employers and actively engaging them in shaping study programs, participating in assessment, etc.

– Enhancing WBL programs by monitoring and evaluation. WBL programs are living objects; they are intended for constant review and adaptation according to technology developments, new social partnership agreements, etc. Colleges should be able to design and use new forms of WBL suited to social, economic and geographic contexts.

– To do so, colleges must invest in training and retraining for their human resources. Like any other model, WBL is only as good as the persons who implement and promote it. To have a stronger and more efficient WBL, the education system must allocate more time and financial support to capacity building for teachers, masters and industry partners (including experience exchange among colleges and lyceums).

– Individual assignments. Individualization of learning in general, and in WBL specifically, is a promising approach in making TVET more attractive and efficient. One singular aspect here is the positive impact individualization can have on improving students’ soft skills and professional maturity.

About the Author

Janyl Bokonbaeva, Ph.D., has 19 years of professional experience in international development projects in education. She coordinates competence-based training for an ADB-financed project “Sector Development Program: Skills for Inclusive Growth” in the Kyrgyz Republic.

1 In addition to level 5 TVET specializations, ten level 4 TVET professions/trades were also supported by the project. This blog focuses on level 5 interventions only.