The Business of Development: The Institutional Rationales of Technology Corporations in Educational Development

In this NORRAG Highlights, Lara Patil, NORRAG Advisor, presents her research on the motivations and rationales of technology corporations in educational development. Given the growing recognition of the role of the private sector in achieving the SDGs, she suggests a need for greater transparency and stronger education sector planning tools to evaluate the opportunities and risks of public-private partnerships in development.

Technology corporations are acting on opportunities to leverage corporate employee skills, products, services and platforms to address distance-learning and educational needs in response to the global commitment to the right to education. By analysing the motivations and rationales of technology corporations in educational development, I sought to advance an understanding of their role in the post-2015 development agenda and how they compare with other actors such as bi-lateral and multi-lateral organisations.

The motivations for this study were personal, arising from the interplay between my parallel paths over the past two decades as an employee of Intel Corporation and as a doctoral student and scholar. Employment at Intel revealed the powerful emerging role of technology corporations as actors in education and development. Contemporary comparative education research in the area of transnational education policy transfer and donor logic provided a framework with which to analyse the observed, increasingly influential role of technology corporations in international educational development. See the recent International Journal of Educational Development publication for further elaboration.

Donor logic

Donor logic – the process of analysing or dissecting various institutional rationales in order to better understand the motivations of actors in the development space – is an established tradition in the field of international and comparative education (Holmes, 1981; Steiner-Khamsi, 2008). By adapting and applying the concept of donor logic to transnational technology corporations, the research builds upon a longstanding research tradition in comparative and international education by bringing the same rigour applied to various actors in international development to transnational technology corporations.

When applying the donor logic concept to transnational corporations, the term “institutional rationale” was used in lieu of donor logic. This decision was based on the following operating assumptions. First, transnational technology corporations operate outside the realm of traditional donors, and cannot be classified as donors because they are profit-seeking. Second, that for-profit philanthropic models, largely pioneered in the technology sector as an alternative to the highly regulated traditional US 501(c)(3) private foundation, are blurring the lines between high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) and the corporations that they found and lead.

Methods

Original research was undertaken during the period 2012-2015, and revisited in 2020/21. Theoretical sampling, data collection and data analysis took place over three rounds. The data set included a total of 30 interviews with key stakeholders from Cisco, Intel, Microsoft, multilateral organisations, NGOs, research organisations, academia and government, as well as participation observation and document analysis. This study required a high level of access to corporate executives and employees, as well as other key stakeholders engaged in partnerships for education and development. This paper leveraged the author’s personal motivation, access and unique perspective.

Institutional rationales and implications

A common dynamic found across Cisco, Intel and Microsoft was the evolution of forms of engagement in international educational development over time. In the past two decades, all three transnationals have moved from promoting their respective individual programmes to more strategic endeavours that aim to identify key intersections between core business and their social engagement to solve global challenges. All three companies transferred education initiatives from their corporate foundation or corporate affairs organisation to the parent company in close proximity to – or actually within – a business or sales unit.

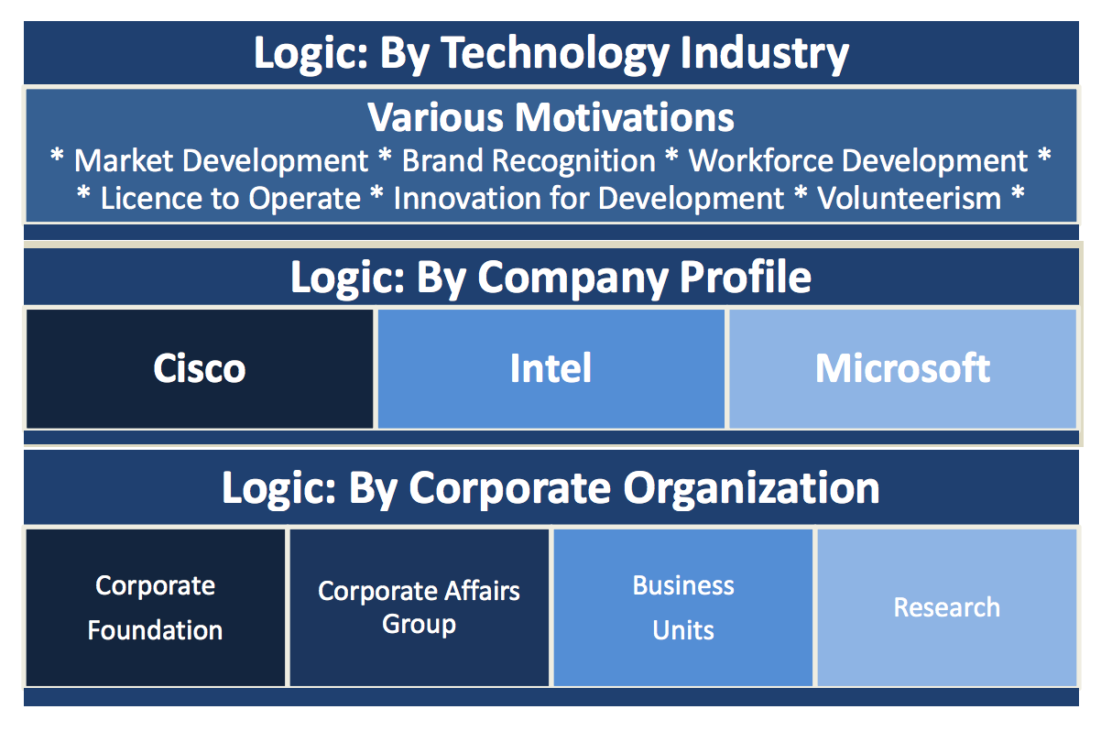

While the research identified common characteristics among the sample of transnational technology corporations, the concluding framework revealed multiple logics for Cisco, Intel and Microsoft’s engagement in international educational development, highlighting the need for nuanced analysis. Institutional logics emerged across three categorical layers: (1) the logic of the technology industry; (2) the logic of an individual corporations core business; and (3) the logic of organisational divisions within the same company.

In regard to the role of technology corporations in the post-2015 development agenda, the analysis concluded that while government bi-lateral aid organisations tie their loans and grants closely to foreign policy goals and multi-laterals make their assistance contingent on specific conditions (Steiner-Khamsi, 2008), transnational corporations engage in international educational development for financial gain. The pursuit of financial gain may take the form of brand recognition, market development or workforce development. These financial incentives vary by industry, company and organisation, and may be direct (i.e. license to operate, market development) or indirect (i.e. brand recognition, volunteerism), short-term (i.e. pilots and ecosystems for innovation in development) or long-term (i.e. workforce development).

These conclusions may seem obvious. The relevance to educational development, though, is two fold.

First, development assistance and national public spending for education has declined, in a context where meeting education targets will require significant increases in spending. The underlying expectation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its supporting background documents is that the private sector will make up much of this gap, either through direct financing or innovation (Draxler, 2020; Education Commission, 2016; UNESCO, 2015; UNGA, 2015). Acknowledging that the core education Sustainable Development Goals recognise the role of non-state actors in the achievement of global education targets, two major international reports published in the past year address the part played by the market, profit and commercial dynamics in education – Reimagining our Futures Together: A New Social Contract for Education (UNESCO, 2021) and Non-state Actors in Education: Who Chooses? Who Loses? (GEM Report, 2021).

Second, international governmental and non-governmental organisations, such as the United Nations (UN), the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), are also increasingly recognising the role of private sector actors by including them in funding, research and agreements. International governmental and non-governmental organisations, such as the United Nations Global Compact and the Abidjan Principles, a recent major civil society initiative to develop norms and standards around private education (Abidjan Principles, 2019), have also developed international instruments to guide and influence public and non-state actors in their practice and policy formation. The challenge for the public-private partnership mechanism, however, is that the motivation and rationale for private sector engagement in the education sector is often unclear (Robinson et al., 2012; Draxler, 2012; van Fleet, 2012).

Conclusion

How and when technology corporations engage in international educational development depends, in large measure, on where momentum for the engagement originates within the company. A lack of contextual factors, such as organisational objectives or the impetus of engagement, can lead to misperceptions in terms of commitment and capacity. The research suggests a need for greater transparency and stronger education sector planning tools to evaluate the opportunities and risks of public-private partnerships in pursuit of development. I believe both are required to address the immediate needs of the global education crisis and work toward the universal goal of the right to education. By advancing understanding of the motivations and rationales of technology corporations as actors in international educational development, the hope is for the development of more effective partnerships through enhanced transparency, legitimacy and accountability. With greater transparency, parties working within multi-stakeholder partnerships for education will be able to react proactively, rather than reactively, to institutional agendas.

The author

Lara Patil is an Advisor to NORRAG, an associated programme of the Geneva Graduate Institute. Lara’s research in the area of donor logic and the role of non-state actors in educational development builds upon academic and professional experience with technology industry giving. She managed global education research, policy and strategy for Intel Corporation for over a decade, and holds a doctorate in Communication and Education from Teachers College, Columbia University.

Email: lara.patil@graduateinstitute.ch

Intuitive and user-friendly investigation/risk detection tool