How Countries and International Organizations Value Education Policies: Introducing the 6Es Framework

In this blogpost, Manuel Enrique Cardoso introduces the 6Es Framework that aims to provide a general, systematic (but not exhaustive) framework to examine the explicit and implicit values that inform policy debates. This blog post is a continuation from our fifth session of the UNESCO Chair Series on Comparative Education Policy held at the Geneva Graduate Institute on April 10, 2025.

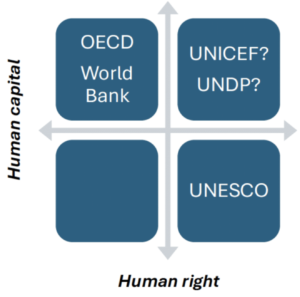

Regarding education policy, different actors assign different value to different values. The human rights approach to education focuses on equality, equity and universalism; while human capital theory sees education as an investment with individual and social returns. International organizations (IOs), oriented by their respective mandates, adopt different approaches: UNESCO, with an education mandate, epitomizes the human rights approach; while OECD and the World Bank, both with economic mandates, embrace human capital theory; other IOs combine them (Cardoso 2020; 2022; Choi 2024).

These differences are not merely rhetorical but affect policy choices that IOs and countries make, for instance, when assessing the literacy and numeracy skills of adults in their households. UNESCO’s LAMP targeted all adults aged 15 and above, thus focusing on universalism and lifelong learning; meanwhile, the World Bank’s STEP targeted urban adults aged 15-64, thus focusing on the working age population, and cities as knowledge economies. Crucially, in this context, developing countries can choose with whom to partner: for instance, Vietnam conducted a LAMP field trial, but later chose to implement STEP instead.

Interestingly, when Choi (2024) examined 178 countries’ discourse on their education reforms between 1960 and 2018, she found that Vietnam was one of the top three countries with the keenest focus on human capital theory. Meanwhile, several Latin American countries, including my native Uruguay (more on this later), alongside South Africa, were among the top ten countries with the keenest focus on human rights and equity. Perhaps not coincidentally and, in a sense, paradoxically, Latin America and South Africa are among the world’s most economically unequal regions and countries, respectively.

But can these different value orientations that shape policy be systematically organized?

Introducing the 6Es framework for valuing education policies (Cardoso 2022)

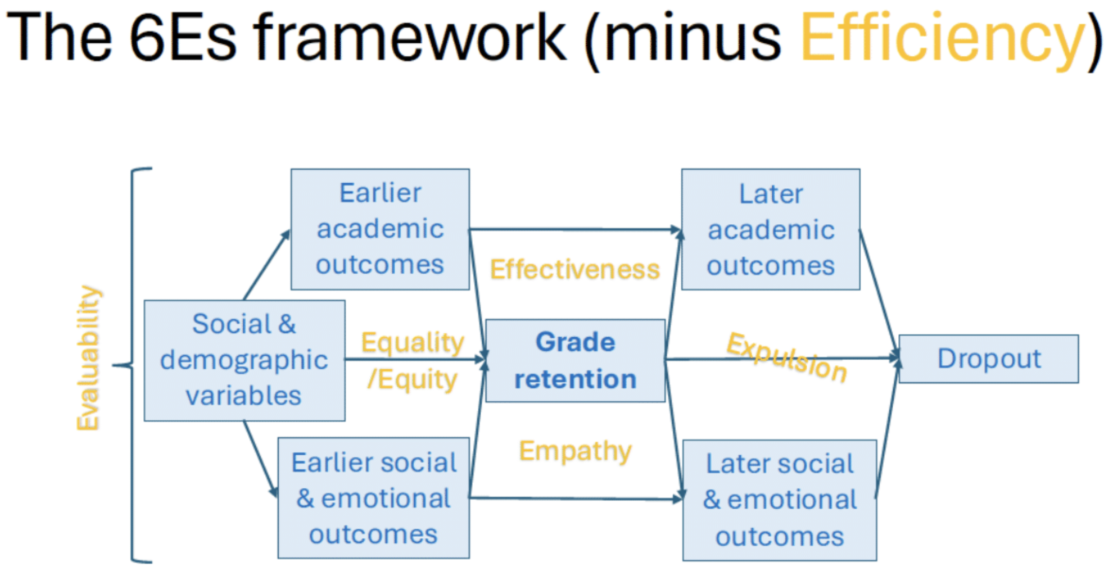

In an English-language literature review about grade repetition (or retention) for my doctoral dissertation, I found mostly critiques, and mainly of six types:

- Effectiveness. Does grade repetition improve student achievement? (Shepard and Smith 1990).

- Efficiency. “What are the costs and benefits?” (Eide and Goldhaber 2005, 195).

- Equality & Equity. “What characteristics are associated with being retained?” (Jimerson 1999, 244).

- Empathy. “What are the emotional effects of retention?” (Shepard and Smith 1990, 85).

- Expulsion. “Is grade retention associated with dropping out?” (Jimerson 1999, 244).

- Evaluability. Is it possible to objectively evaluate the impact of retention? (Allen et al. 2009).

Effectiveness: relationship between grade retention and later academic outcomes, with or without controlling for earlier academic outcomes (which makes a huge difference, since retention is often remedial). Efficiency (not pictured in the diagram): relationships between repetition’s costs and benefits; but both OECD and the World Bank actually defined inefficiency as involving repetition (Emmerij 1967; Haddad 1979) even before there were reliable cost-benefit analyses (Eide and Goldhaber 2005). Equality: link between social background variables (e.g., gender, socio-economic status) and repetition; equity introduces prior academic outcomes as controls, given the practice’s remedial nature. Empathy: link between repetition and social or emotional outcomes. Expulsion: (causal?) link between repetition and dropout.

Finally, Evaluability refers to the challenges in evaluating the impact of grade repetition on academic achievement, socioemotional outcomes, and dropout. As a remedial practice, it is only applied to a relatively small subset of students, who are not representative of the overall composition of schools (in academic, sociodemographic and/or socioemotional terms), and are nested in classrooms where most of their classmates are not retained but can still be indirectly impacted. In this process, repeaters are separated from their networks and reinserted into other classrooms, also creating a dilemma: who should they be compared to, their former classmates, or their current ones? All of these features raise methodological difficulties and questions that, ultimately, may not have a unique, objective answer (Allen et al. 2009).

Overall, this figure (inspired by path diagrams, for those readers familiar with them) has a veneer of scientism (i.e., the appearance of being scientific and rigorous). Crucially, concepts like each of the six Es, while originating in supposedly rigorous studies, end up making their way into the policy and political debates. There, they can be framed and reframed in a number of ways, while lending legitimacy to those who use them.

For instance, Reducing repetition: issues and strategies illustrates how different IOs frame efficiency: UNESCO published it, but a World Bank officer wrote it. The preface, produced by UNESCO, asks “how many more pupils could be enrolled” (p. 9) if repetition was abolished, showing an underlying focus on equality and universalism, features of the human rights approach. Meanwhile, the author himself, Thomas Eisemon (1997), again, a World Bank officer, is more interested in “trade-off in public investments among sub-sectors or types of training” (p. 15); replacing education with training, thus pivoting to the world of work, as in a human capital approach.

Different professional cultures also emphasize and frame each of these issues differently. The review showed how many education technocrats doubted grade retention: economists concerned with efficiency (e.g., Eide and Goldhaber 2005); sociologists with equity (e.g., Cadigan et al. 1987); and psychologists with empathy (e.g., Jimerson et al. 2002). But teachers themselves are underrepresented in academic discourse about repetition, and few scholars admit that repetition “may also reduce heterogeneity of academic achievement within those classrooms, which may arguably make instruction more efficient” (Hong and Raudenbush 2005, 205), especially for teachers.

Simultaneously, the issue of tensions and tradeoffs between these values, e.g., equality and efficiency, has a long and controversial history (see Okun 1975). But in contexts of automation, supposedly incompatible values like equality and efficiency appear to reconcile. Some International Large-Scale Assessments (ILSAs) claim that AI-based “automated scoring holds promise as an efficient method (…), costing less and running faster than human raters” (Jung et al. 2025, 2), while also arguing that it “should focus on consistent and accurate assessment within and across countries rather than simply emulating human scoring” (Jung et al. 2025, 11), thus implying that it can also be more equitable, fair and just than humans.

Another technology-focused example, Uruguay’s One-Laptop Per Child, illustrates a further complexity: policy debates revolve around the “Es”, but also around disagreements about a policy’s intended outcomes. There is wide agreement that Uruguay’s nationwide, equity-minded One Laptop Per Child initiative (Plan Ceibal) increased technology access. However, scholars found no impact on learning (De Melo et al. 2013; 2017), but… was that an intended outcome? Others find declining proportions of students choosing STEM fields in college (Yanguas 2020). Overall, a focus on explicit versus implied outcomes is another source of disagreement in policy debates.

Examples of different impact on values and outcomes in Uruguay’s One-Laptop Per Child:

| Access to Technology | Learning | Other Education Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effectiveness | (+) | De Melo et al. 2013, 2017 (0) | Yanguas 2020 (attainment 0; field of study -) |

| Equity | Diaz et al. 2022 (+) | Yanguas 2020 (attainment 0) |

Concluding remarks

In considering education policy alternatives, different actors (domestic and external) assign different value to different values. For instance, some IOs like UNESCO see education mainly as a human right, prioritizing equity; others like OECD and the World Bank see it mostly as human capital, emphasizing efficiency; yet others (UNDP, UNICEF) combine both perspectives. At the same time, developing countries can choose, to some degree, the external actors with whom they partner, thus emphasizing different values and outcomes.

In this context, the 6Es aim to provide a general, systematic (but not exhaustive) framework to examine the explicit and implicit values that inform policy debates. Using it as a checklist, however, would just scratch the surface: as seen, merely namechecking a value is not particularly revelatory, since each can be framed in different ways, thus reshaping the policy discussion. Moreover, when discussing the impact of a given education policy, especially in hindsight, actors can strategically “move the goalpost” by focusing on different outcomes from the ones originally and explicitly intended.

While the 6Es were originally identified in academics’ discourse about grade retention; I have since found them in policy debates involving other stakeholders and policies. This framework enables us to systematically describe arguments that various actors use in either advocating for, or criticizing, different policy solutions. Some questions remain: How do actors resolve tensions between values? And when a policy addresses a wide range of values, is it more likely to succeed in finding support among wider coalitions?

The Author:

Manuel Enrique Cardoso is Head of Research at the Institute of Education, Universidad ORT, Uruguay. He has a PhD in Comparative and International Education from Teachers College/Columbia, and an Ed.M. in International Education Policy from Harvard. He worked as a learning specialist in the UN system for nearly two decades, first at the UNESCO Institute for Statistics in Montréal, and then at UNICEF’s headquarters in New York. He previously held several research, teaching and professional positions in Uruguay, the United States and Canada. His work has been published in the Comparative Education Review, the International Review of Education, and Compare, among others. His research interests include international organizations; national and international large-scale assessments and education policy; and language(s) in education.