AI and Children's Rights

In this blogpost, which was previously published in NORRAG’s 4th Policy Insights publication on “AI and Digital Inequalities”, Sonia Livingstone and Gazal Shekhawat call for a global public debate that includes children’s ideas about how to develop AI in ways informed by children’s rights.

When OpenAI launched ChatGPT in November 2022, calls to ban its use in schools were immediate, preceding careful consideration of the educational or participatory benefits of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) for children. The response to technological innovation was a media panic that blamed industry for being irresponsible and children for cheating, with policy being formulated largely in the absence of either evidence or child consultation. ‘Twas ever thus.

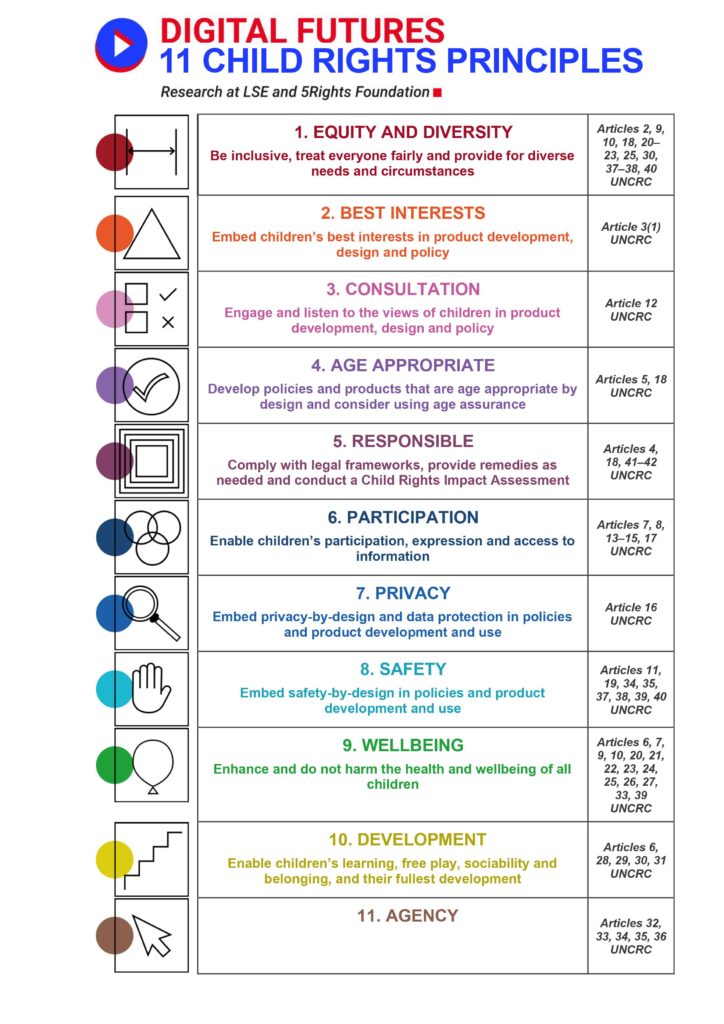

Yet there is now a substantial body of AI guidance informed by children’s rights, most notably, UNICEF’s (2021) Policy guidance on AI for children. In the same way as generic frameworks, child rights–specific guidance also prioritises principles of inclusion, explainability, fairness, privacy and accountability. But crucially, such guidance spells out ways to explain and implement these principles in ways that respect the full range of children’s rights according to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, countering the temptation for adults to speak for children without consulting them, presume children need not be asked for consent or are incapable of giving it and overlook the ways that children can be vulnerable to unfair, invasive or unaccountable actions without remedy. All this notwithstanding that people under the age of 18 comprise one in three of the world’s population.

What does a child rights–respecting approach to AI look like in practice?

The World Economic Forum’s (2022) Artificial Intelligence for Children Toolkit urges businesses to adopt a labelling system (via product barcodes or QR codes) to warn of potential AI harms, data processing and age-appropriateness. While this relies on self- regulation, an alternative approach is to rate those businesses independently. In 2023, akin to nutrition labelling, Common Sense Media started to rate AI products independently via its AI ratings system to inform parents and educators about product ethics, transparency, safety, privacy, bias, fairness and impact. This has the merit of independence but the problem of scale, for it is largely privileged parents who will be aware of such an offer.

Another powerful approach could involve setting standards, as illustrated by the IEEE (2021) Standards Association’s Age-Appropriate Digital Services Framework. The advantage is that while businesses may or may not decide it is in their commercial interest to comply, public services (schools, health, care, transport, etc.) could choose (or be required) to comply with AI product standards and build them into their public procurement, thereby raising the bar for all AI-related services likely to have an impact on children’s lives and perhaps also persuading investors and venture capitalists to rethink their priorities. However, it is also clear that the direction of travel, at least in the US and Europe, is for AI-specific regulation, although this often includes little or no mention of children apart from some hand waving at children as the future or, at best, a discussion on safety or education (though rarely both).

What does good look like?

Take the case of the educational technology being rolled out by governments worldwide. While it is clear that investors and Big Tech stand hugely to gain financially and acknowledging the importance of sustaining children’s learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, research on educational technology delivering the promised benefits to learning, inclusion or even accessibility, not to mention cost-effectiveness, is oddly unconvincing. Nor is it clear that personalised learning is ideal, that education chatbots improve outcomes or that AI-driven emotional or cognitive profiling in the classroom merits the huge extraction of children’s personal and even sensitive data (Livingstone & Pothong, 2022). When AI guidance provides case studies, these tend to be more compelling regarding the risks (of abuse, disinformation, discrimination, exploitation) than the opportunities—especially if we require opportunities for them to be fairly available rather than exacerbate digital divides.

When it comes to AI and children’s rights, crucial questions for research, policy and practice remain unresolved. Should we put our weight behind the (largely voluntary but specifically tailored) approaches to AI and child rights or would it be more effective to advocate for legislative initiatives (albeit that these tend to regulate AI generically, with little provision for children)—or, most likely, both? Also, can child-rights advocates rebalance the focus of guidance to include but also go beyond the avoidance or mitigation of AI-related harms to explicate the still-vague and insufficiently evidenced presumption that AI deployment will bring desirable outcomes that fairly benefit all children? For anything more—and the big picture is still hard to see (i.e. will AI help us with the end of work, overcoming inequality or saving the planet?)—we need a global public debate, and such a debate must include and listen to children too.

Key takeaways:

- To make some headway on immediate practices and processes, policymakers should deploy established child rights approaches (for a rationale and toolkit, see the Committee on the Rights of the Child’s General comment No. 25, 2021).

- To keep a holistic and grounded vision, incorporate Child Rights by Design in the commissioning, development and use of AI (Livingstone & Pothong, 2023).

- To grasp in detail how all this can specifically apply to AI, review the available child rights guidance (Shekhawat & Livingstone, 2023) and apply child rights impact assessments.

About the Author:

Sonia Livingstone, The Digital Futures for Children Center and London School of Economics and Political Science, UK

Gazal Shekhawat, The Digital Futures for Children Center and London School of Economics and Political Science, UK