Counting for Change in Gender and Education

In this blogpost, which was previously published on the GPE KIX website, Elaine Unterhalter, Rosie Peppin Vaughan, and Helen Longlands consider gender and education data in relation to global policy frameworks.

This year we move beyond the mid-point of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) era, which means it is time to start reflecting on what shape a post-SDG agenda might take. Data, which provide the information that is collated for the SDG indicators, and the systems associated with those data have been a central component of the SDGs and the policy directions they mapped. The data have helped to enrich the informational base and deepen reflections about how to move from policy to practice. But the large array of data systems associated with the SDGs have created a mixed picture of gaps and successes. Underinvestment in national statistical offices in many countries has made it difficult to deliver on all the data referenced in the SDG framework. This situation has prompted many discussions about how to provide for a prospective range of new indicators associated with a post-SDG agenda and what they should track. A parallel issue is the need for a discussion about how the next range of indicators should be decided. Such discussions can feel overwhelmingly complex, but we should not let that complexity turn us away from the ambition that informs the SDGs and will, we hope, also inform any post-SDG framework. We should not shy away from the analytic and strategic problems entailed in improving data and measurement processes.

In this blog post, we consider gender and education data in relation to global policy frameworks. This relationship has been debated since the 1990s, the time of the Education for All (EFA) and Millenium Development Goals (MDG) frameworks (Unterhalter & North, 2017). How can we connect thinking about data, which might describe gender inequalities or equalities in education, with thinking about accountability to deliver on equity and eradicate injustices? Some analysts argue that data can support structures that are concerned with increasing access to all levels of education, enhancing the quality of learning and teaching and ensuring outcomes that are associated with flourishing and well-being (Schleicher, 2018). But they also point out that data cannot in and of themselves build institutions, support fair relationships within institutions and deepen insights into how institutions can help people thrive and work to change the many forms of insecurity and inequality that confront us. Many of those who want to collect only a minimal amount of data for a post-SDG framework also make this argument.

A new approach to data to improve inclusion and equity

Gender and education is a particularly important area in the context of improving data and creating and implementing policy and practice that affect inclusion and equity and are guided by data. Gender equality has been a priority area for policymakers for over two decades, with girls’ education and empowerment being frequently hailed as “silver bullets” for eradicating poverty and supporting a host of other positive development outcomes (Unterhalter, 2023). Yet while there have been improvements in headline measures concerned with gender equality in access to schooling, in participation in school and in learning outcomes, many forms of gender inequalities in and through education persist. For example, some children still experience gender-based violence (GBV) at school, and in some education systems, teachers and administrators have limited knowledge about how to put policies regarding support and protection into practice. Certain groups of girls or boys may also find their choices about what to study are limited by gendered expectations. Entrenched gender stereotypes continue to exert an influence after girls and boys have left school; they may find their employment and further education options are also restricted by gendered expectations. Such inequalities relate to wider structural gender inequalities and the actions that reinforce and reproduce them. Current metrics focus disproportionately on achieving gender parity (i.e., equal numbers of boys and girls) in enrolment and completion, and in basic educational indicators such as reading. On their own, these are not adequate for documenting and tracking the form of intersecting inequalities or their complexity. We need more involvement from a broad range of groups with insight into these gender inequalities in education and discussions about what needs to be measured, how existing data can be used to better effect and what new data could be collected.

GPE KIX Bridging AGEE project

We believe there are innovative, democratic ways of creating and using data to support better engagement at different levels and for collaboration among different actors working to transform gender inequalities. The Accountability for Gender Equality in Education (AGEE): Bridging the Local, National and Global project, which is supported through the Global Partnership for Education Knowledge and Innovation Exchange (GPE KIX), a joint endeavour with the International Development Research Centre (IDRC), is being implemented as a partnership between researchers at University College London (UCL), UNESCO and the University of Malawi. Researchers on the Bridging AGEE project are working in collaboration with governments in Indonesia, Kenya and Malawi to reflect on the gender and education data that exist, what data are missing and how to connect national data systems and the policies and practices that build on them. A crucial aspect of this project is that it will invite and listen to local views about addressing marginalization and exclusion in communities marked by these processes. The project seeks to build a community of practice that sees the process of reflecting on what data are needed for guiding policy on gender equality in and through education as a crucial part of building the institutions and supporting the actors that can establish and advance relationships of accountability and responsibility for the transformation of unjust structures and relationships.

The GPE KIX Bridging AGEE project draws on ten years of work to formulate and validate the AGEE Framework (see Figure 1). The framework applies a multidimensional understanding of gender equality in education and where inequalities might persist and is divided into six domains. Each domain has a structured AGEE participatory process for how indicators are to be identified and selected. The AGEE Framework directs attention to building a dashboard, with indicators that do not only comprise a number of widely used education indicators relating to participation and learning outcomes, but also encompass information about resource and structural constraints, values, opportunities and a wide range of health, employment and well-being outcomes from education.

Figure 1. The AGEE Framework

Each AGEE domain brings together indicators that concern an aspect of policymaking, contextual information and practice. The process of reflecting collaboratively on these indicators is associated with building relationships to foster accountability. In each AGEE domain, reflective discussions and critical reviews, conducted over the past decade at both national and cross-national levels, have involved more than 1,000 participants from over 50 countries. The participants represented government departments, civil society, women’s rights advocacy groups, youth organizations and activists, multilateral organizations, academics and students. The outcome of these processes was a collection of appropriate indicators to create an AGEE Dashboard of gender equality in education. Cross-national dashboards that compile data from a cross-national database covering 47 countries are set to be published in March 2025. Through the Bridging AGEE project, national AGEE workshops, held to date in Indonesia, Kenya and Malawi in January and February 2025, have begun surveying national gender and education data landscapes. The workshops were grounded in the AGEE participatory approach and aimed to support the development of national dashboards. In addition, in each country, four neighbourhood dashboard workshops will be launched in 2025. They will focus on identifying what data are needed to understand local gender inequalities in and through education and will explore strategies to overcome them.

The relevance and significance of the indicators

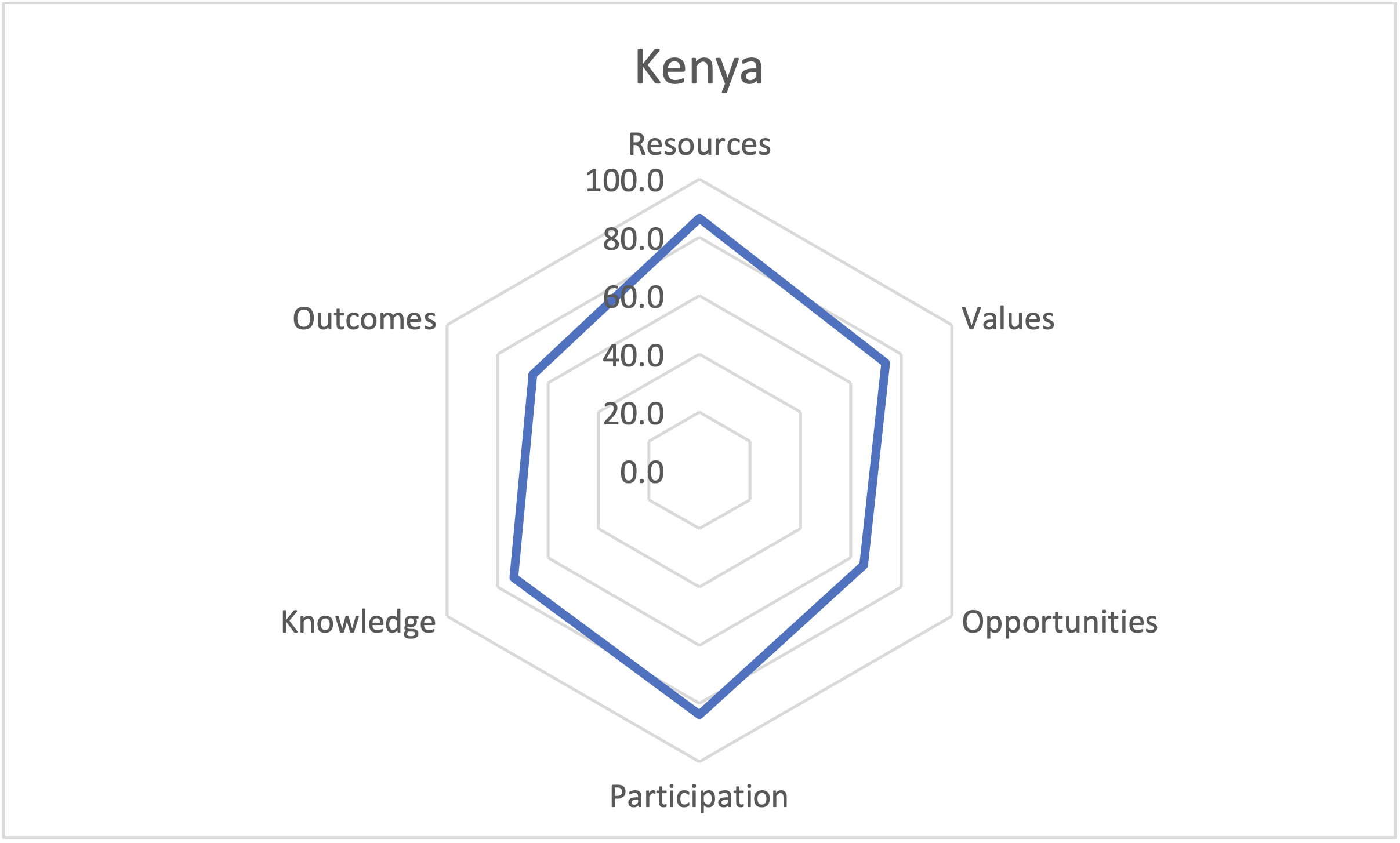

Indicators associated with the AGEE cross-national dashboard highlight some important areas for action. Figure 2 below presents two diagrammatic representations for country Spotlight Briefs for Indonesia and Kenya, two of the countries with which Bridging AGEE is currently working. In compiling data for these country-level visualizations of the cross-national dashboards, we drew on a manual collation of the data available by country and held in cross-national databases. The data span a range of dates, but the most recent data point available for each country was used. In the radar graph representations of the AGEE Framework, the values for each indicator range from 0 to 100. Some indicators have had to be rescaled. For further information on the process of assembling and scaling data, see our Technical note to accompany the AGEE Spotlight Briefs.

Figure 2. AGEE domains and values for Indonesia and Kenya