Learning Poverty When Schools Do Not Teach in Children’s Home Language

In this blogpost, Maya Alkateb-Chami presents findings from her comparative research on the correlation between linguistic discordance and learning poverty.

Education is a fundamental human right and a cornerstone for societal development. These tenets are widely accepted today, but one significant barrier to education is often sidelined in broader conversations about access to education: schools’ language of instruction. My research at the Harvard Graduate School of Education has identified a strong correlation between lower literacy outcomes at the country level and a misalignment between students’ home language and the language of instruction at school, a phenomenon I refer to as linguistic discordance, borrowing a term from the medical field.

A significant portion of students globally—at least 40%—are taught in a language they do not speak or understand best. This may seem like a high percentage, but after accounting for children who are schooled in their country’s historic colonizer’s language and the cases of linguistically minoritized communities, which include traditional linguistic minorities in addition to immigrants and refugees, this figure seems to be an underestimate.

With World Bank data showing that in 2015, 48% of the world’s young learners were not developing foundational literacy skills, a figure likely exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, I analyzed data from 56 countries and delved deeper into two country cases to see if linguistic discordance is linked to these outcomes. My quantitative data came from a recently curated data set by the UNESCO Institute for Statistics as well as from the World Bank.

The importance of language-in-education cannot be overstated. Literacy development builds on prior knowledge, including general background knowledge and knowledge of language itself. When children are taught to read in their first language, their existing knowledge of the world and language is mobilized to foster proficient reading. However, when students face linguistic discordance from the onset of schooling, they face a significant challenge: the learning scaffolds they have in their first language are not adequately capitalized upon or expanded for literacy development either in their first language or in a second language.

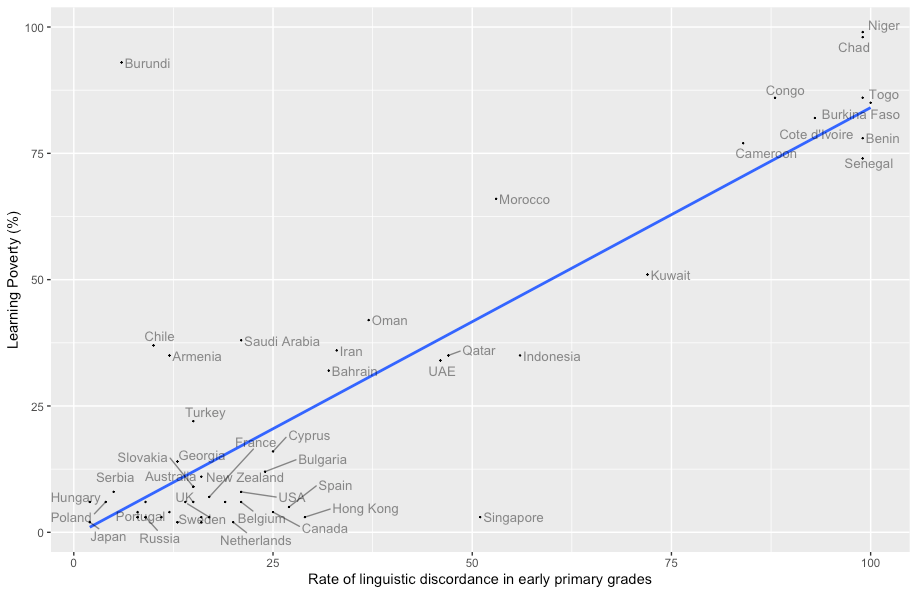

The study revealed a strong, positive correlation between the rate of linguistic discordance per country on the one hand, and Learning Poverty on the other—where Learning Poverty captures the rate of students per country who are unable to read and understand a basic text by age 10. In other words, countries with higher percentages of children who experience linguistic discordance tend to have higher Learning Poverty rates, whereas those with more students who are schooled in their home language exhibit lower Learning Poverty.

New comparative study reveals a robust positive correlation between the rate of linguistic discordance (when schools do not teach in children’s home language) in early primary grades and Learning Poverty (a country-level basic literacy measure) across 56 countries. This graphic was originally published in the International Journal of Educational Development here.

While this trend is consistent across the sample of low-, middle-, and high-income countries, aligning with and augmenting findings of existing research, it presents as most pronounced in middle-income countries—a new insight in the field. I will highlight from the full analysis offered in the paper that the language of instruction is not a magic wand and there are other variables, extreme poverty for example, that contribute to lowering educational outcomes in low-income countries. On the other hand, high-income countries enjoy factors such as higher teacher proficiency in the language of schooling that contribute to reducing the strength of the (still strong) association in those contexts.

Furthermore, the study underscores the importance of looking into local contextual factors beyond general trends. For instance, in Singapore, despite a high rate of linguistic discordance, the country has low Learning Poverty rates. Conversely, Burundi has high illiteracy rates despite most of its young children having their home language as the language of school instruction—two cases that are investigated in the study as trend outliers.

In addition to the role background knowledge plays in facilitating language and literacy development, it is crucial to consider that literacy development is a cross-curricular endeavor, in which not only the quality but also the quantity of exposure to and engagement with written text mediates early reader success. This makes attention to policies and practices related to language of instruction, compared to those in relation to teaching language as a subject, even more critical. The impact of language of instruction on learner motivation (by way of influencing early reader success) as well as on the quality of teaching are also elaborated as part of the study’s theoretical backbone.

Findings call for serious attention to the issue of linguistic discordance in policy and research toward the achievement of providing—at least basic—literacy for all. While the importance of the language of instruction question has been highlighted across contexts, research has been concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. The present study’s wide comparative perspective offers fresh insights on the topic and emphasizes the need for prioritizing language of instruction-centered policymaking, interventions, and research globally. It also points to the immediacy of needing interventions that are informed by existing local and comparative research.

In addition to increasing attention to linguistic discordance across country income groups, findings suggest that policy interventions promoting instruction in a student’s first language in middle-income contexts could yield the most improvements in basic literacy outcomes compared to other settings. They also call for decoupling low- and middle-income countries when analyzing educational interventions and outcomes toward the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal 4: Quality education.

Read the full paper in the International Journal of Educational Development, where it is available with open-access until February 24, 2024.

About the Author:

Maya Alkateb-Chami is a Doctoral Candidate at Harvard University. Her research is concerned with the role of schooling in fostering equitable and just futures, with a focus on literacy education, language of instruction policies, and epistemic justice.