The Limitations of Foundational Literacy Metrics

In this blogpost, which is part of NORRAG’s “Missing Education Data” blog series, Hamza Sarfraz and Zain Ul Abidin argue that “foundational literacy” and “learning poverty” are based on unreliable metrics that potentially misrepresent the actually existing learning situation in any particular context and risk leading to misguided education policy and resource allocation.

As the deadline for 2030 looms ever larger with each passing year, there has been a worldwide intensification of efforts towards achieving the key targets set within Sustainable Development Goal 4. Some of the targets that have become increasingly essential to these efforts are linked to the notion of ‘foundational literacy’.

As the World Bank reported in 2022, 57% of the children in low- and middle-income countries were unable to acquire minimal proficiency in literacy by the age of 10. Often dubbed as ‘Learning Poverty’, this phenomenon has continued to gain traction and has been progressively foregrounded in the discourse on education amongst governments and international development partners. In turn, this has led to increased resource allocation and emphasis on metrics associated with literacy.

Given the reported situation for foundational literacy across the globe, this is understandable. For instance, within Pakistan—home to 66 million school-aged children and one of the biggest recipients of global education financing—the current learning poverty figure stands at 78%, which amounts to nearly 4 in every 5 children being unable to read a simple text by the age of 10. This evidence-base has provided the thrust towards Pakistan’s latest Federal Foundational Learning Policy 2024. Within sub-Saharan Africa, the figures for learning poverty shoot up to 86%, which is now being directly addressed by policies, sector plans, and programs throughout the region.

On first look, this data on foundational literacy hints at a very troubled situation across the majority world that requires a sustained response. However, as we highlight in this blog, these figures merit a deeper look. The increased emphasis on foundational literacy, based on learning poverty as a key metric, is inevitably linked to policy priorities, resource allocation, and education data regimes. For instance, as of 2023, this has led to policy efforts in 86 countries and catalyzed funding of around $16.5 billion. These high stakes raise some critical questions.

First, where exactly is the evidence for learning poverty emerging from and how reliable is it? Secondly, even as this evidence drives contemporary educational policy and financing efforts, how much do the metrics underpinning it capture the varied literacy contexts within which children from the majority world learn? Third, is this drive towards foundational literacy coherent with and/or cognizant of other challenges in educational service-delivery within the majority world, including teacher training, early childhood education, inclusion, and budgeting etc.?

In this blog, as we focus on the first question, a good place to begin with is the literacy data that provides the basis for calculating, or more accurately, estimating learning poverty globally. Within the broader context of missing data in education, well covered in NORRAG already, it is worth asking how the data collection, analysis, calculation, and reporting of literacy happens within specific contexts.

But before diving into the particular challenges associated with emphasizing Learning Poverty as the go-to metric for educational policy making, it might be useful to see how much credible literacy data actually exists within global education data regimes. Among the most trusted and recognized sources for globally benchmarked and comparable education data is the database for World Development Indicators, curated by the World Bank. We are particularly interested in looking at literacy situation within the world, as captured in the data that is collated, recognized, and deployed by the World Bank and other major educational stakeholders, who are also driving the current focus on Learning Poverty.

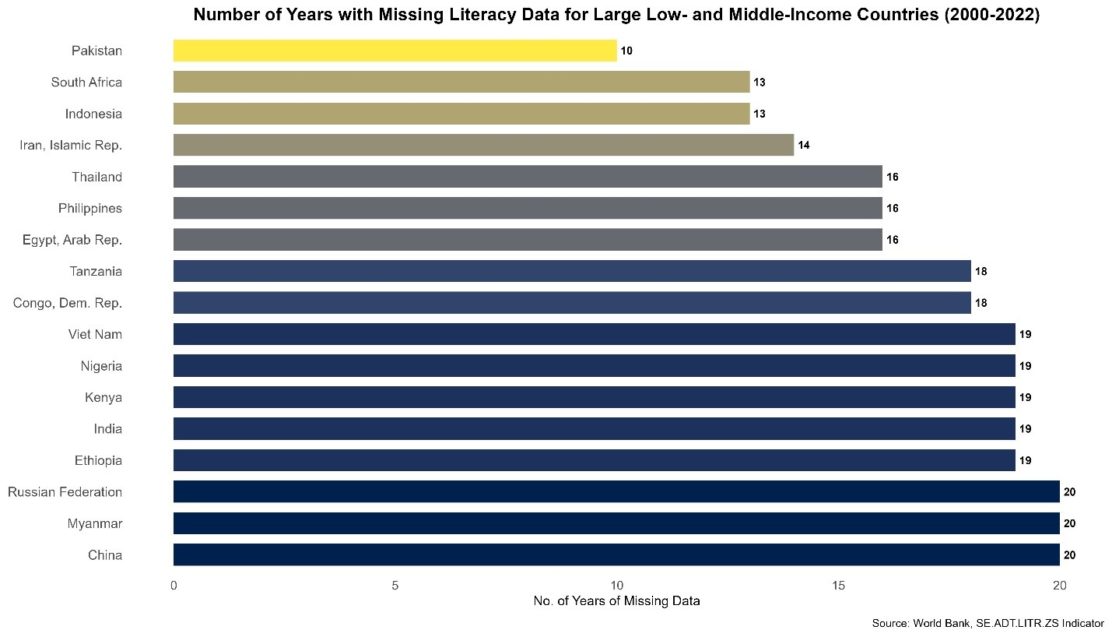

A preliminary look into the database reveals something rather strange. Even if we focus on just the 21st century and filter down data for only the most populous low- and middle-income countries in the world, the amount of missing data on literacy is striking. In fact, as the following figure showcases, most of the populous countries, which together contain the majority of the global population, have a significant number of years with missing literacy data.

It is critical to note that some form of data on literacy for all of these countries exists, but that it isn’t necessarily recognized as credible by education data regimes. Given the increased demands for rigorous and meaningful education metrics, it is possible for global education data regimes to exclude any doubtful and low-quality data. But if there is so much of missing quality data on literacy over the past two decades across majority of the world, where exactly are the figures for Learning Poverty coming from? And more importantly, how can we establish their credibility, veracity, and usefulness for educational decision-making?

This then brings us to the major concerns regarding the Learning Poverty metrics: their methodological limitations, particularly as they relate to the underlying data from which they emerge. There are three interrelated challenges here. As their own reporting shows, whenever global stakeholders—including the World Bank and UNESCO Institute for Statistics—gather evidence on literacy, they generally address the missing data through extrapolation, estimation, or proxy techniques. These techniques roughly estimate literacy levels for countries with missing data by extrapolating it from available information, either within or across countries.

For instance, in countries like Pakistan and Nigeria, where large-scale literacy assessments are either sporadic, outdated, or unreliable, the Learning Poverty figures may reflect collated regional averages rather than specific, observed evidence gathered through rigorous student-based assessments. This reliance on estimates is understandable within a globalized drive towards SDG reporting, but it carries a major risk of misrepresenting the actually existing learning situation in any particular context and undermines their use-case as a reliable evidence-base for driving education policy and resource allocation.

Beyond estimation, the Learning Poverty metrics also face sampling challenges. Much of the data Learning Poverty relies on comes from large-scale assessments like PISA, TIMSS, and regional evaluations like SACMEQ and PASEC. In the absence of these, national assessments are utilized. Currently, there is an ongoing discussion on building consensus towards harmonizing these diverse assessment tools but the inherent difficulties remain. Regardless, most of these assessments do not necessarily gather regular data from children outside formal schooling and/or on the margins (including refugee camps) in low-income countries. These also the groups where data gaps are the most pronounced.

Furthermore, the specific but narrow focus on reading proficiency at age 10 may provide for a global comparative, but it’s usability as a policy-defining metric is not without challenges. While reading proficiency is undoubtedly an essential component of foundational learning, other critical domains such as numeracy, socio-emotional growth, and problem-solving are currently neither captured nor addressed by Learning Poverty metrics. This focus on a specific skill at a single point in a student’s journey overlooks variations in school systems, such as different school entry ages or progression rates, especially in countries where grade repetition is common or where children enter school late. It runs the risk of neglecting broader improvements happening within the local systems.

Taken together, these methodological concerns suggest that Learning Poverty figures might not accurately reflect the realities for learners across the globe and like any metric, they should be deployed carefully in guiding educational policy that impacts hundreds of millions of learners. In fact, most of these concerns have been actively acknowledged by the key stakeholders involved and the efforts for more accurate metrics are ongoing. And yet, the limited data from Learning Poverty continues to serve as a key evidence-base and rallying point for educational policymaking in many countries in the majority world. Governments and international development organizations rely heavily on these figures to drive resource allocation, formulate national education strategies, and monitor progress toward global agendas such as the Sustainable Development Goals (especially SDG 4).

This overreliance on an evolving, but flawed, set of metrics risks leading to counterproductive policy measures—focusing on quick fixes for reported literacy rates while overlooking deeper, systemic issues like teacher training, infrastructural deficiencies, equity and inclusion concerns, and socio-political barriers to universal learning. As we’ve discussed previously on NORRAG, there is a tendency among global education stakeholders to enforce their own data regimes over the rest of the majority world, which in turn has major repercussions for learners and communities directly impacted by it.

Otherwise, it is possible to achieve successful reporting for SDGs targets through these metrics, without directly addressing the problems they were meant to solve.

The Authors:

Hamza Sarfraz is an education data practitioner and researcher from Pakistan. He currently manages impact and evidence-building at a learner centric education company. Previously, he was involved with ASER Pakistan and co-authored the country profiles on Pakistan for the GEM Reports 2020 and 2021.

Zain Ul Abidin is an education policy researcher and practitioner currently working as a Data Analyst at the University of Glasgow. He is interested in global education policy, international development, girls’ education, and Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion. His work on the second chance education program with Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi was recently awarded as one of the top 100 education innovations by HundrED.org.