Ukubaluleka kobuchwepheshe : Ethical AI as a Tool for Decolonizing South Africa’s Early Childhood Development Sector

In this blogpost, Sithole kaMiya argues that AI presents a unique opportunity to reverse the historical trend of marginalizing Indigenous knowledge in South Africa’s education system, with a focus on early childhood education. However, it is vital to ensure that AI will not be used as a tool of assimilation but as a force of cultural preservation and empowerment. This blogpost is part of NORRAG’s Early Childhood Education, AI and the digitalisation of education and #TheSouthAlsoKnows blog series.

The release of ChatGPT in November 2022 marked a turning point in integrating Artificial Intelligence (AI) into education. For some, AI promises a future of personalized learning, addressing students’ needs with precision. For others, it poses a threat, deepening social inequalities, reducing education to data points, and perpetuating Western-dominated, colonial frameworks.

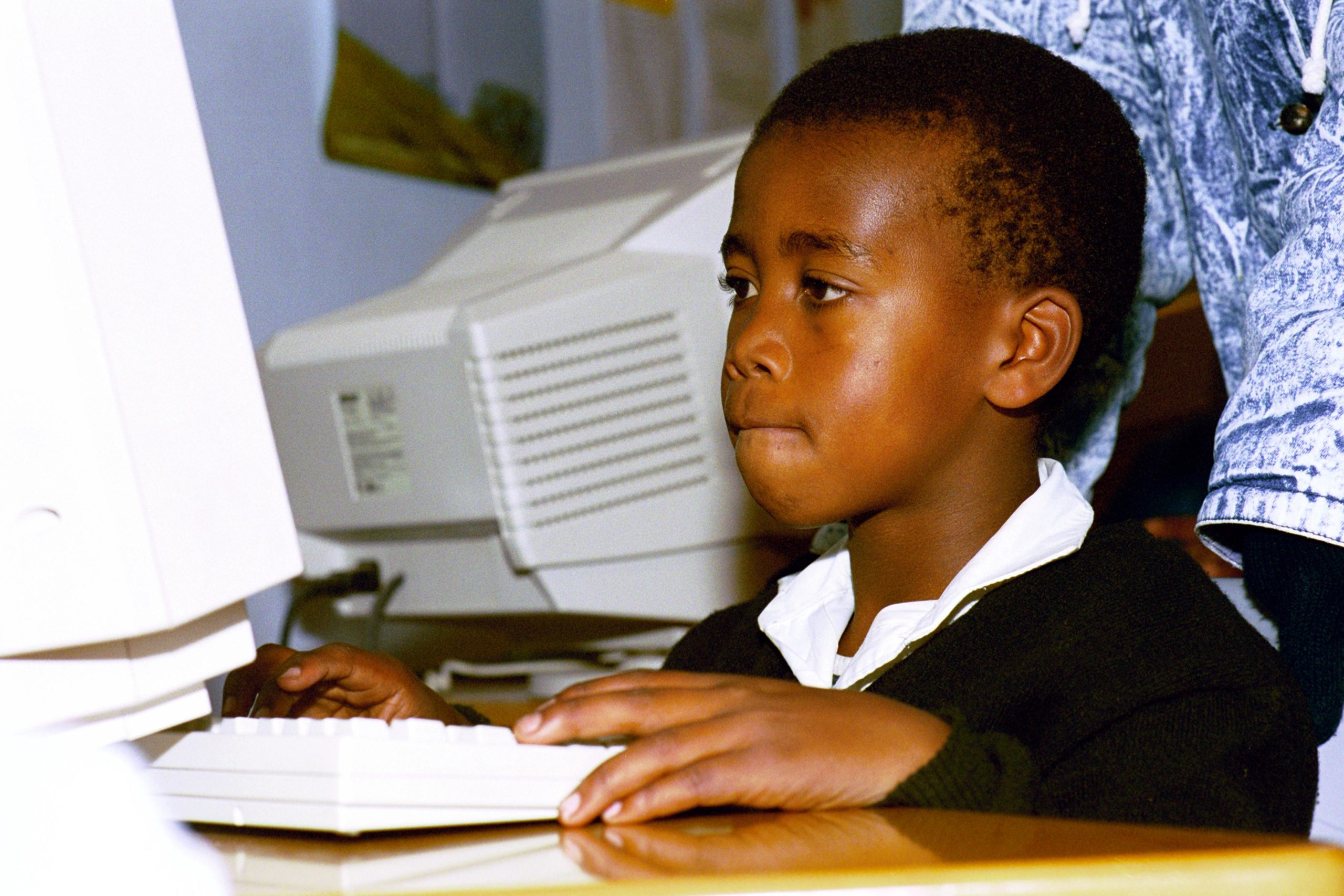

In South Africa, AI’s application in Early Childhood Development (ECD) offers an opportunity to reimagine education by prioritizing decolonial values rather than replicating outdated models. With the potential to provide culturally relevant, individualized, and accessible learning experiences for historically marginalized communities, AI could transform ECD. However, this potential depends on designing AI tools grounded in equity, cultural identity, and community input. Without this, AI risks perpetuating the exclusion of Black South Africans’ voices, languages, and experiences.

Personalized Learning or Cultural Erasure?

The idea of personalized learning is often sold as one of AI’s greatest strengths. AI platforms can track each child’s progress, adapting lessons to their unique learning styles, developmental stages, and pace. But as we look at South Africa’s deeply fractured education system, personalized learning must go beyond simply tailoring instruction to academic performance. The true radical potential of AI lies in its ability to help children connect to their languages, histories, and cultures, all of which are frequently neglected in the mainstream educational system.

Take Ubongo Kids, an African-based platform that uses AI to offer personalized content to children across the continent. This platform adapts learning to a child’s pace, making sure each child is engaged. However, despite its potential, one critique of Ubongo is that it still largely serves urban, middle-class families, and it struggles to integrate local languages and cultural contexts into the curriculum. As of 2022, the total number of schools in South Africa amounted to nearly 24,900. The majority of these schools were public entities, covering around 90.8 percent of the total number of schools in under-resourced areas; this presents a challenge: How can AI be used to personalize learning for children in rural areas while staying true to their cultural context?

A decolonial approach would ensure AI adapts not just to performance but to cultural relevance. AI tools should teach South African children about local heroes, histories, and traditions. For example, platforms like Ubongo Kids could incorporate stories from local icons in languages like isiZulu, isiXhosa, and Sepedi, moving beyond a Western curriculum. This would foster pride, identity, and personalized, engaging learning rooted in the child’s reality.

According to the 2011 Census, 86% of South Africa’s population speaks an African language as their first language, yet most education systems still prioritize English or Afrikaans. AI could be a powerful tool to support home-language instruction, bridging the gap between students’ first languages and the academic language used in schools. By using AI to create personalized, multilingual content, we could foster a generation that feels deeply connected to both their local culture and the globalized world.

Localized AI: A Radical Reimagining of Educational Equity

Educational inequality remains a major challenge in South Africa, especially in rural areas and townships. While AI promises to enhance access and outcomes, many children lack the devices, internet, and tools needed to benefit. The true potential of AI lies in its ability to be localized and accessible to underserved communities.

Consider SmartStart, an innovative, low-cost ECD program operating in rural and township areas. While SmartStart uses simple technology, it is poised to benefit from more advanced, AI-powered interventions. SmartStart reaches over 130,000 children in South Africa, many of whom live in remote areas. AI could enable SmartStart to develop personalized learning pathways for each child, tracking their developmental progress and providing tailored interventions. For example, AI tools could monitor children’s interactions with learning materials and provide educators with real-time recommendations on how to address specific learning gaps. In areas where teachers often lack the necessary training and resources, AI could function as a supplemental tool, empowering educators and improving overall learning outcomes.

The success of AI In education depends on affordability and accessibility. A 2022 report by Alliance for Affordable Internet shows that there is a 79.7% meaningful connection gap with an estimated percentage of rural population with meaningful connection in South Africa. AI solutions must work offline to serve children in remote areas, ensuring personalized learning reaches all communities.

The Ethical Dilemma of AI: Surveillance and Datafication

A key ethical concern with AI in education is data privacy. AI tools collect extensive data on children’s learning and behavior, which, if misused, can reinforce inequalities, enable surveillance, or violate privacy. In South Africa, with its history of inequality, AI risks becoming a tool of control rather than empowerment.

South Africa’s Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), which came into effect in 2021, lays down regulations for data protection, but it is unclear whether this framework can adequately protect the data of young children in ECD settings. As AI platforms in education continue to expand, data-driven practices will be increasingly central to how children’s progress is assessed, but the data they generate must be treated with the utmost care.

Take the example of Biometric Attendance Systems, which have been used in some schools in South Africa. While these systems aim to improve attendance rates, they also raise privacy concerns. Biometric data, which includes fingerprints and facial recognition, is highly sensitive and prone to misuse. Extending such surveillance systems into the ECD space could result in the normalization of surveillance practices from a young age, raising questions about the ethics of collecting such personal data without informed consent from children or parents.

To use AI in a decolonized, radical way, data collection must prioritize identifying educational needs, tracking progress, and ensuring equitable support—not control or for the sake of efficiency. Local communities should guide data decisions, ensuring it serves children’s education rather than corporate or state interests.

AI as a Tool for Cultural Reclamation and Community Empowerment

The radical potential of AI in ECD lies not just in its ability to personalize learning, but in its power to support cultural reclamation and community empowerment. South Africa’s education system has historically marginalized Indigenous knowledge systems, and AI presents a unique opportunity to reverse this trend. By embedding cultural context into AI-powered educational platforms, we can create learning environments that reflect the lived realities of South African children.

The African Storybook Initiative, which offers multilingual digital stories for young children, serves as an example of how AI can be used to integrate local stories, languages, and values into the curriculum. While still in its early stages, this initiative could expand by incorporating AI tools that personalize the delivery of stories based on a child’s learning preferences, pace, and interest. Such tools could be used to teach both formal academic content and informal lessons on local culture, ensuring that AI is not a force of assimilation but one of cultural preservation and empowerment.

Moreover, Ilifa Labantwana, a South African organization focused on improving ECD, could leverage AI to scale its impact. AI tools could be used to analyze data from across the country and identify areas where ECD services are most needed. This data could help policymakers allocate resources more equitably, ensuring that children in underfunded communities have access to quality education.

Conclusion: A Radical Future for AI in ECD

Artificial Intelligence can transform Early Childhood Development in South Africa, but its impact depends on its application. If shaped by an inequitable system, it will reinforce injustices. However, as a tool for cultural reclamation, educational equity, and empowerment, AI can serve marginalized communities. By making AI culturally relevant, locally developed, and ethically governed, we can create a decolonized education system that meets the needs of all children. AI in ECD is not utopian—it is a radical opportunity waiting to be realized.

The Author:

Nkosana Sithole kaMiya is an IAPSS-Africa Regional Public Relations Officer as well as a Research Fellow of the WITS Society, Work and Politics Institute (SWOP) doing research under the “Violent State, State of Violence” project. He is also a GLUS Sue Ledwith awardee and Mellon Development Program Research Fellow funded by Andrew. W. Mellon Foundation. His research interests are in the Intersectionality of Epidemics and Development, Decolonial Pedagogy, and Political Theory.

Notes:

- The importance of technology (translation from isiZulu to English)