Using Data for Accountability

This Blog Post is contributed by Angela Arnott, an education Policy Analyst from Southern Africa and working across Africa, as part of the NORRAG Blog Series on Missing Education Data which aims to further explore six themes that emerged from the inaugural summit and its accompanying papers and expert consultations. In this post, the author looks at gaps in the use of education data by citizens and civil society for accountability.

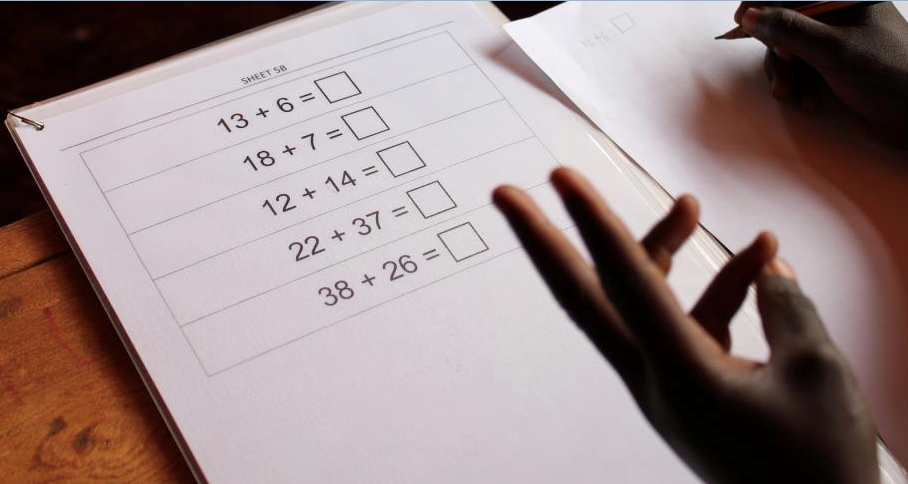

Why do our societies accept that 98 million children on the continent are out of school[1] and 193 million children of primary and lower secondary school age will reach their adolescent years unable to read, write or perform basic numeracy tasks[2]. What are possible solutions that could address this absence of a culture of accountability? Why is it that the use of data and measures of performance of the education sector are seldom used by communities in Africa to hold their governments accountable?

There are countries where school children consistently underperform and there is no reported national outcry. In 2010 Malawian primary school children were the worst performers in literacy and numeracy in a group of African countries tested[3]. Among the causal factors listed was high teacher and learner absenteeism and inequitable pupil/teacher ratios. School community engagement was suggested as a solution. By 2015, the situation had not changed and the majority of learners had not achieved the minimum basic competencies as specified by the National Primary Curriculum across 4 subjects. Most scored below the 40% mark despite increased government expenditure on teachers and infrastructure[4].

We know at least a third of people, 15 years and older are unable to read and write. Some 40 percent of girls and women are illiterate. We also know almost 60% of Sub-Saharan Africa’s population is under the age of 25[5], making Africa the world’s youngest continent as well as being the least educated. Young ill-educated parents are not best placed to engage in public debate on access to quality of education issues when sustaining a livelihood for their families is pressing. African parents do track exam results as these are high stake gateways to other avenues of education and training but seldom use these and other data to hold their governments accountable for producing a quality education system for all.

Few African governments measure their performance by systemic learning achievement assessments. Only a quarter of African countries have provided comparative learning assessment data since 2014. Governments and development partners have tended to focus on visible indicators such as infrastructure, teachers, books and enrolment. These are inputs and outputs rather than outcomes. There is no doubt school enrolment levels have been rising over the years as a result of government interventions on fee-free education. The assumption has been that having children in school will, automatically, lead to learning. This assumption has led to an invisible problem of children being in school and not learning.

There is a need to provide simple understandable measures that civil society can use to hold education decision makers accountable and lobby for change. Standards are one mechanism of promoting accountability and high performance in education, particularly for people living in poor communities where schooling options are limited. Those people may be unaware that the schooling provided to their child is of low quality, or they may interpret the data on their child’s performance against national examination averages as a reflection of their child’s cognitive abilities or choices, not the quality of resources provided and managed by government.

UWEZO, a citizen-led assessment movement operating in East African countries proved that a significant number of children exit primary education without having ever attained the basic competences, contrary to their school leaving certificates. UWEZO established that 3 out of 10 Ugandan Primary 7 students were unable to read and write at a Primary 2 level, attributable in part to the uneven distribution of teaching and learning resources regionally with similar results in Kenya and Tanzania [6]. Although UWEZO has succeeded in disseminating its findings widely in these countries, the shock value of low learning levels in schools has diminished in the current public discourse. Recent research[7] argues that although there was a shake-up in the Ministries of Education’s comfort zones, subsequently there has been minimal engagement in public discourse with their social accountability for poor delivery and further the UWEZO community engagement philosophy and discourse has not led to citizen action on a national level.

Education systems should set simple standards and, just as importantly, communicate these standards to parents so that they may better understand their child’s progress and hold schools accountable. Indexed school averages or school improvement rankings[8], with all their drawbacks of not addressing uneven playing fields, are nevertheless useful mechanisms for promoting civic awareness of school accountability and performance. Evidence on the use of school report cards that profile the schools performance and resources relative to surrounding schools and national averages indicates that when communities are provided with information on the local education situation, access, enrolment and learning outcomes improve[9] Easy-to-use profile cards, accessible to low-literacy audiences, help parents, teachers and students stay informed and hold school managers and local officials to account.

School governing bodies should be provided with data on how their schools performed relative to each other. Schools performing poorly should get pressure from governing bodies or school communities. Such pressure may become political when parents and learners realize they are being short-changed by resource allocations. Or it may become market pressure as parents and learners recognize new indicators of performance and choose schools based on evidence rather than hearsay and anecdotal measures of performance. This is low-level political accountability. Schools performing poorly should feel market pressure from parents voting with their feet, and, if they do not have enough pupils, should perhaps be shut down. Building such a culture of accountability will ultimately place political pressure on senior policy makers to more effectively manage resources and monitor more closely their promised political aspirations.

About the author

Angela Arnott is an education Policy Analyst with decades of experience working in Africa on building effective education management information systems for policy support and assessments at national, regional and continental levels.

References

Harvey Goldstein and Sally Thomas. (1996) Using Examination Results as Indicators of School and College Performance. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) Vol. 159, No. 1 (1996), pp. 149-163 (15 pages). Published By: Wiley

Jeremy Monk. (2020)Placing Blame or a Call to Action? An Analysis of Uwezo in the Kenyan Press. Education Policy Analysis Archives. Volume 28 Number 185. Teachers College, Columbia University.

Mary Goretti Nakabugo (2015) Twaweza East Africa. Towards Equitable Quality Basic Education in Uganda: Insights from Uwezo Learning Assessment Data

CICE Hiroshima University, Journal of International Cooperation in Education, Vol.17 No.2 pp.23 ~ 35

Government of the Republic of Malawi (2019) Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology. Malawi Education Sector Analysis. Lilongwe, Malawi

The Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (2020): Africa SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2020. Kigali and New York: SDG Center for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

PAL Network. (2015) CITIZEN‐LED ASSESSMENT: MALAWI CONCEPT NOTE

Footnotes:

[1] UNESCO, Global Education Monitoring Report 2020: Inclusion and Education: All Means All (Paris: UNESCO, 2020), p. 210 <https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000373718> [accessed 8 September 2021].

[2] Brookings. (2015)The Center for Universal Education (2013) This is Africa Learning Barometer survey https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/too-little-access-not-enough-learning-africas-twin-deficit-in-education/ estimated 61 million primary school learners in this category. However https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-04/ propose that non‑proficiency rates are highest in sub-Saharan Africa, where 88 per cent of children (202 million) of primary and lower secondary school age were not proficient in reading, and 84 per cent (193 million) were not proficient in mathematics in 2015.

[3] World Bank (2010) quoting SACMEQ 111 results on literacy and numeracy.

[4] Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2015) Malawi Monitoring Learning Achievement.

[5] https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brookings-now/2019/01/18/charts-of-the-week-africas-changing-demographics/

[6] Mary Goretti Nakabugo (2015)

[7] Jeremy Monk. (2020)

[8] In Tanzania, Under Big Results Now Initiative, School Improvement Grants, issued to increased performances based on a list of criteria, gain huge attention in the public media.

[9] UNICEF (2019) Data Must Speak.